There a numerous sins in role-playing games and one of them is railroading. Railroading is such a sin that some people go out of their way to prove their approach at their table roots out railroading with puritanical zeal devising models of play that allegedly ensure the players can just pursue any random whim unfettered by even the slightest pre-destined restriction.

As such, a commonly held belief is those pursuing the goal of an intentional story at their table must be committing the foul sin of railroading in order to achieve that?

The truth about intentional story

The purpose of this post is to demonstrate why the below statement is true.

Approaching role-playing games with the goal of having an intentional story does not necessitate railroading. In fact, to truly achieve an intentional story railroading is impossible by definition.

Experimenting with the practice of intentional story in role-playing games has been something I’ve been playing with across my 37 or so years in the hobby, but what recently inspired this post is thoughts on how plot and story aren’t the same and how it is this essential mistake that causes the railroading myth.

I posted a bit about it on social media but this place is always for the more robust version.

The plot v story error

We are going to break the argument down, but it’s worth covering the key mistake people make first. The reason people religiously believe an intentional story at the gaming table has to feature railroading is born out of not recognising the difference between plot and story.

The belief goes something like this. The story is the plot, so a plot has to exist for an intentional story to exist and that plot is the GM’s job ergo heavy railroading down a pre-determined plot has to exist. Some people argue back, and I used to be one of these people, how that plot can be pretty mutable in response to player decisions, but even that is the wrong argument.

Neo: What is the truth?

Young Monk: There is no spoon.

– The Matrix

If you truly recognise the difference between plot and story and how engaging fiction actually works and apply it to role-playing games only the nugget of a concept of a plot has to be pre-agreed at the table or possibly even no plot at all for an intentional story to happen.

And you know why this is definitely true? To get that answer we can look at the anatomy of a story.

The Anatomy of A Story

I’m a big proponent of reading books on how fiction is constructed, whether with the goal of writing a novel or a script or just from the viewpoint of marketing, and then translating that knowledge into how it would be applied to the role-playing game experience.

One book I happened to read recently, in a very serendipitous moment after putting my thought on Twitter, was Wired for Story by Lisa Cron and it allowed me to firm up my embryonic thoughts by breaking down the anatomy of a story.

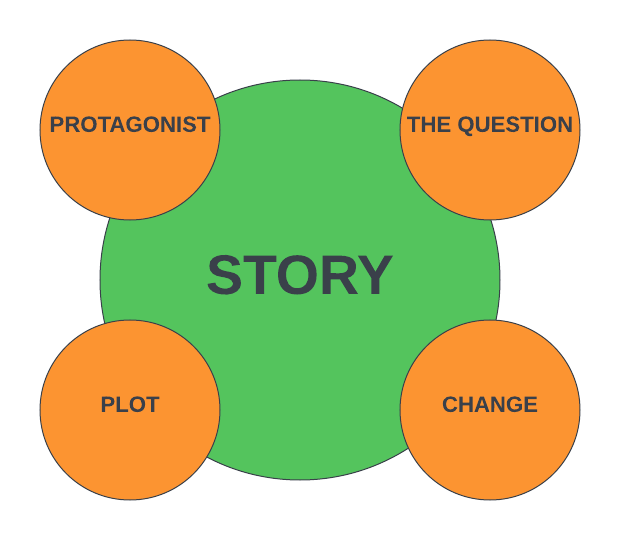

A story isn’t just something that happens, or what happens to someone, or even what happens dramatically to someone it is ‘what happens to someone who is trying to achieve a difficult goal and how he or she changes as a result’. The four parts of the anatomy of a story support this.

We can look at each of the elements in turn.

The protagonist is the someone and they are also the person trying to achieve the goal. What is this in role-playing game terms? It’s the player characters, of course. It’s important to recognise that a protagonist in a story is not a normal person.

The question is the goal. What burning question is the protagonist trying to find an answer to? It may not be the answer they want but they will find it (or not finding it is an answer in itself). This question can be articulated in numerous ways but one way is through the concept of each protagonist having a premise . I created a character to fit into this anatomy of a story understanding for a current D&D game I’m involved in.

The change is how the protagonist changes in order to find the answer to the question and / or upon finding it.

The plot is what happens, but what happens is constrained by a lens and that is what happens serves to support and drive how the protagonist changes.

The key thing to take away from this is what the story actually is. It’s not the plot, but how the protagonist changes in relation to their goal. Basically, the element of change is the story the rest just supports or gets the protagonist there.

Wait a second, who controls this story?

The plot, in role-playing game terms, is the element that needs the least definition, to the extent it need not be determined in advance at all, for the anatomy of a story to work.

Now, take a second to look at the four elements that make up the anatomy of a story and ask yourself, even in the most traditional of role-playing game experiences, who controls each area?

Yes, that’s correct, three of the four pillars on which a story is based are in the player domain. Only the plot is traditionally in the GM domain. The player creates the protagonist, the player will decide what their driving question is and the player will ultimately decide, albeit influenced by events and other characters, how their character changes.

If the players’ aren’t delivering on this you only have a plot, probably delivered by the GM. This is what leads to the argument of railroading, the players abdicating their responsibility, or the GM ignoring them for his plot but the truth is a plot, in role-playing game terms, is the element that needs the least definition, to the extent it need not be determined in advance at all, for the anatomy of a story to work.

So, how does this actually work?

If the plot is the least important element of the anatomy of a story in a role-playing game how does the whole thing actually work? It’s hard to write it out as an exact set of instructions, as running a role-playing game is certainly a practice, where tools and techniques are used to achieve your outcome, but there are certain methods you can use.

Players? Step up

The balance has to shift to the players and the players need to step up. In order for what actually constitutes an intentional story to exist the protagonist have to have that why. The burning question they are seeking an answer to. This should be more than a goal, such as re-take my kingdom. The good thing is we have a method for this, the concept of protagonists being burdened with premise.

Let’s consider that example of someone trying to re-take their kingdom. Possibly their premise could be: –

External: Re-take the thrown of the Sea Elf nation

Internal: Am I a great leader like my father?

Philosophical: Win the nation? Lose the civil war?

As you can see this becomes more complicated and isn’t just about acheiving the external goal but goes on to establish some of the burning questions that will probably feed into how the character might change.

We can do the same for a popular character in fiction, let’s say Luke Skywalker:-

External: Must defeat the empire.

Internal: Am I a Jedi?

Philosophical: Can good defeat evil without becoming evil?

It can be seen how these questions are answered when Luke throws his lightsaber aside instead of killing his father when he finally has the upper hand, even though this puts him in a situation where he might actually die at the hands of the Emperor.

The intentional story truly is in the players’ hands, the GM just provides material for them to work with.

Playing to find out

What counted as plot was a rolling example of playing to find out as things happened from an initial heist that started in media res as the first scene. The story was how the protagonists answered there meaningful question and changed as we played to find out.

Do we really need a plot established in advance or can we just play to find out? I know, it sounds pretty drastic and hard to imagine depending on your approach to role-playing games so far, but it is entirely possible.

Let’s go with an example of a recent Blades in the Dark game, a game of fantasy cutthroats, thieves, insurgents and heists. The game was run over the course of a single day.

We all turned up and we decided on our characters on the day. We decided what the goals of our crew would be on the day. So, the idea that the protagonists would be fighting as insurgents for the freedom of another nation wasn’t known until that actual morning. So, the plot was a rolling example of playing to find out as things happened from an initial heist that started in media res as the first scene.

Where was the story? It’s my view the game’s story came down to the traumas the characters had on their character sheets. It was these traumas that caused all the elements that were the actual story. The fact the crew went to rescue a kidnapped friend. The fact one crew member bailed on that rescue due to them being cold-hearted while another character was too good for the cause she was embroiled in. The decision to let others kill an enemy because she couldn’t do it herself and so on. The traumas were getting in the way of the protagonists achieving their broader goal of freeing an oppressed nation.

That was the story, the playing to find out of the plot largely serves to drive those protagonist decisions and changes and to give the players situations to insert them.

The importance of the emotional why

I’m a big fan of this one. All great stories are not about how and what they are about why. They are also about the emotional why. That’s what draws us in. I also believe the emotional why boils down to relationships between people, institutions and ideas.

Always know the emotional why at all times and at all levels.

Why is this important? Because how and what elements are very hard for the players to use when looking to attach their protagonist’s question or premise to, but an emotional why is golden. A character who has been historically abused will find it hard to connect to the cloistered ex-wife of a gang leader, but they won’t if the emotional why is the gang leader is controlling and the ex-wife wants out. Use the emotional why to establish links, parallels or subtexts to the characters’ personal questions is literally what you have to do to turn the mechanical plot, however it origins, into fuel for protagonist change.

I use this tool a lot, it was one of the primary methods in the Werewolf Accelerated game I last ran (basically a distilled Werewolf: The Apocalypse second edition campaign using Fate Accelerated).

This is also one of the most important tools when running an adventure module that comes with a lot of pre-determined plot. If you’re not wanting to throw all that pre-determined plot out you are, to some extent on rails, but what you can do is find the emotional why in the events and try to make that appealing to the burning questions inherent in your player characters. That way the pre-existing plot is still allowing them to drive their change.

The power of situation

Always presenting situations without defined endings or conclusions is another tool to use. You leave how the situations will resolve in the hands of the decisions the players will make and the dice as what this does is give the players the space to insert how these situations relate to their character questions and in turn how it might change them.It helps if, as the GM, you are responding to the protagonist’s signals when you are creating these situations.

This was another tool used in that Werewolf Accelerated campaign. Lots of the scenes in the game were situations layered with the potential for the characters to explore their burning question. It was true the characters didn’t always have clear signals of what their burning question was, but some clarity could be implied, and I would just leave that space hanging as a calling card for them to insert themselves into it. I’d then respond to that.

It’s a mixture of responding to signals and playing to find out but with less of a blank slate.

Less plot more antagonism

Don’t sweat how the players do things or find their way to your situations or areas in a sandbox. In fact, the plot the GM brings to a game should be less about a route map and more about disconnected elements the players will route through and ensuring there is antagonism to meet whatever and however they choose to do things.

As long as the antagonism that rises to meet them is challenging, the situations have enough space or hooks to allow them to insert their premise and how it might lead them to change and there is enough emotional why (or its leading to an emotional why) the players should find a way if an intentional story is to work.

This also helps the story have a narrative velocity with less time wasted on minutia and more time focused on exploring and transitioning to those moments that contribute to a platonist’s ultimate journey of change.

Is it all just signals?

There is an argument to say how the whole table plots to drive this intentional story is actually a function of reading and responding to layers of signals. The signals can come from the characters, their premise and discussions from session zero. Decisions are made by players in the game. How everyone responds to antagonists resisting their endeavours.

It’s all signals which can be used to create new situations to drive out that change.

The critical thing? If you’re responding to a delivered signal, even if it is all the way back in session zero, your response in terms of ‘what comes to constitute plot’ is not railroading as it was clearly signalled as wanted. I’d even go as far to say ignoring the signals is the railroading.

Sandbox and intential story

Let me step back and address the elephant in the room. Don’t the two premise examples given earlier suggest that some idea of a plot exists even if it isn’t mapped out on rails? True, an empire has to exist for Luke to overthrow and the sea elf nation has to exist to be retaken. It’s also implied both will need to be addressed.

I’d argue we’ve not said how or in what way though, which is more of a plot. In truth, you could create the questions differently and run with a complete sandbox, though I admit the external questions would be the ones needing the most adjustment. As an example, you could go for more general causes than specific implementations of the causes.

The sandbox game is often spoken of in terms of it being the complete antithesis of an intentional story. This can be true if that is what is desired, but it doesn’t have to be true. Since the most important elements of a story are in the hands of the players all we are doing in a sandbox is giving them complete control of where they go and what they choose to interact with to find answers to their question and how their characters change!

It is true, that if the GM decides to not engage with those questions at all, or not provide the space for the players to do so, things will be more challenging, but engaging with each protagonists question does not invalidate the truth of a sandbox game and the freedom of player choice, no defined plot map and things happening whether the players interact with them or not.

The truth is the sandbox game is perfectly compatible with an intentional story, or it can be, and is just another way of working without a set of rails.

And, Finally…

The idea that having an intentional story in a tabletop role-playing game, by definition, means railroading has to exist, is based on a false premise and that false premise has a foundation in the mistaken belief the plot is the story and that, in the medium of role-playing games, that plot is even the most important element of a story.

The truth is it’s not.

The most important elements of a story are all in the creative control of the players. This is true to such an extent that the plot should be flexible to those elements or even not known much, if at all, in advance depending on the group’s comfort level. Even a sandbox game can have an intentional story without breaking the sandbox convention because ‘where the story is at’ has nothing to do with a mapped out plot.

That is why pursuing an intentional story in a role-playing game, by definition can and should defy railroading.