This is the first part of a two-part article series that seeks to take a campaign that has been played to completion to demonstrate how various methods and approaches we talk about on social media and the web on a regular basis, including this very website, were practically used and how the campaign turned out.

This is the first part and deals with what went down before the dice were rolled.

Obligatory Disclaimer

The whole approach outlined here is dictated by one simple fact: the campaign’s outcome was an intentional story. If you have a different goal in actual play then it may limit some of the things you can take away from this article.

None of the ideas in this article are meant to be THE way, but I’m not going to make things hard to read by putting caveats in every other paragraph. You can use your imagination to put them in.

Everything in this article was the outcome of a group of five people at the table. It was a group effort. It’s by no way an attempt to demonstrate some Auteur GM story. The very opposite in fact.

The Breakdown

I’ve broken the article down by the pre-play elements: –

- It’s a practice

- The initial idea

- The system

- Session zero

- My anxiety and fun

- Planning horizons

- Planning structures

These elements did not happen entirely in this order.

It’s a practice

People do a disservice to running role-playing games when they say it’s a skill. It’s not a skill it’s a practice.

Like other practices, such as Project Management or Business Analysis, it’s actually a range of skills, tools, frameworks and approaches that are assembled together uniquely each time to achieve an outcome. This outcome is also more likely to be achieved if you have a high performing team.

These articles demonstrate that by showing a range of things intentionally done before and during play.

The initial idea

I’d always wanted to run an epic Werewolf: The Apocalypse campaign but I never got the chance. I tend to like the core ideas of a lot of White Wolf games more than their implementation.

The idea was simple. Take the core principles of what makes Werewolf: The apocalypse great and use Fate Accelerated to create an ‘inspired by Werewolf: The Apocalypse’ campaign using a fiction first system. The voluminous canon would be dealt with by adopting the same strategy Doctor Who took when it re-launched in 2005: non of the canon necessarily exists until events bring it in.

I did write a few goals down shortly after I started and these were: –

- Run a campaign that is distilled and pure Werewolf: The Apocalypse

- Incorporate the inspirations of God of War (video game), Thor: Ragnarok (film) and 4th edition Dungeons and Dragons (RPG).

- Deliver a campaign with depth and weight

- Avoid the feeling of it being a series of one-shots

- Focus on how characters relate to people, ideas and institutions

- See if this fiction first lark works for me as much as it should

- Complete the campaign and stick the landing

This was going to be a Viking epic about a culture that had potentially failed itself, fighting one battle against one potential apocalypse that could bring about the end of times.

The system

The system was Fate Accelerated. I’d been modelling Werewolf in Fate Core but I went with Fate Accelerated for a few reasons.

I’d seen some White Wolf characters done for a one-shot one of the players had done for a convention and they seemed pretty neat.

The game we’d played previously was Dresden Files Accelerated which does an amazing job of adding a number of tools to the toolbox of Fate Accelerated that proved very useful for an inspired by Werewolf: The Apocalypse game.

I did have a number of extra Fate books, a key one was the Fate Adversary Toolkit. While it was for Fate Core everything was transferable and it demonstrated a surprising amount of fictional forms that could be taken to bring the antagonism into scenes. It’s a very cool book.

I didn’t try and convert Werewolf: The Apocalypse as that’s too much effort. I didn’t convert any specific rule from the original game. I relied fully on the fiction first elements like aspects, stunts and tracks to deliver an inspired by approach to the original game.

Session Zero

People can often be prescriptive over what session zero should look like. That’s the wrong approach. The only important thing about session zero is WHY you do it not necessarily HOW you do it. It’s that practice element again, you’ll assemble the tools, approaches and frameworks to achieve the why.

The importance of session zero is to establish clear signals ahead of actual play so everyone is reacting to and authoring on the basis of the same signals.

In our case the assembled elements were: –

- A campaign guide PDF

- Discussions on the gaming groups forum

We didn’t have formal minutes or a 24-page worksheet like I’ve seen suggested on the internet. We went from the above tools to creating characters and running the first session in the same afternoon.

The Campaign Guide

Campaign guides tend to come in two forms: dense bibles full of lore that needs to be absorbed or guiding principles and communicated signals. In our case, it was definitely the latter.

The campaign guide was six pages long but even that is misleading: –

- Front cover (1 page)

- Character monologue (1 page)

- Setting (2 pages)

- Character rules (2 pages)

Looking at it now the character monologue did a good job of signalling the werewolf nation may itself be at fault due to its past actions and decisions. That part is much stronger than I remember as I felt it was just setting tone but it was more than that.

The character rules included a few core werewolf stunts, rage tracks and rules on how werewolves take damage from mundane weapons and regenerate. I also set out I wanted the majority of the characters to be actual werewolves, not other were-creatures.

The setting out of a contemporary adjacent setting, now but also sort of not now. Think something like Chilling Adventures of Sabrina. The technology was a bit early 90’s and the tone was that of the 80’s: greed is good, partying at ground zero and rebellion with an appetite for destruction. I got that 80’s tone of greed and nihilism from Shadows of the Century.

A core of the rules proved superfluous. We didn’t use the mundane damage and regeneration rules. We didn’t really use the rage recovery rules. Half the group were not werewolves. The stuff establishing the tone of the mundane world proved irrelevant. Why this proved to be true came about in the opening sessions, and we’ll cover that in After the Dice Dropped. Does this make the campaign guide a wasted effort? I don’t believe so.

First, it established signals. While some of the specifics, like rules, might have proved superfluous the signals set out in the guide and the discussions born from it were not. It created a situation for good, productive authoring so everyone can enhance what was happening at the table.

Second, these signals delivered early benefits with fantastic protagonists in the form of the player characters.

Third, in a lot of practices, the process is sometimes more important than the artefact created. This is the case with campaign guides, especially ones based on principles more than encyclopedic details. While some of it proved to not be necessary, working through it created a solid grounding in my head of what I wanted to achieve so I can flexibly and dynamically develop from it.

Game Discussions

In order to get to actual play fast the consensus was we’d create characters and play in the first session. That made me nervous. It was a favoured way of doing it of one of the gaming group. I preferred to have the characters and go away and think.

Why did I opt to go with a method I didn’t prefer? Because I wanted to deliver on this campaign and I couldn’t say my methods were working currently. There was a risk I’d go away with the characters and that is where it would stop. So I decided to step up myself and commit to creating characters and playing in the same afternoon.

We discussed character ideas on the forum which meant people were at different stages with their character by the time the first session came around. Some had effectively made them and put them in the forum, some had yet to do it. All were involved in the discussion. Once we got to the session creating the characters was done from a potion of shared strength with us just needing to finalise details and harmonise things as a group.

It was a full, frank and shared discussion which always gets results, but there is one element worth calling out.

I got two werewolves and two other were-creatures. Not a majority. Another player had speculated on playing a different were-creature but went with a werewolf, potentially because of the ‘majority werewolf rule’. By the time we were four episodes into the campaign, I had only one werewolf character out of four. The reasons for this are covered in After the Dice Drop. It suffices at this point that you can sometimes set up rules on character types because you think it’s important but ultimately you find the best version of the story at the table is to break that rule.

My anxiety and fun

It’s worth being honest about something before we get into the parts about how I planned the campaign ahead of the actual play.

I did it to control my anxiety and enhance my fun.

My life has been a journey of learning the tools from experience, my career and education to be able to plan and design while (1) just knowing enough and (2) ensuring I am building to what I need to know in the future without panicking about it.

What’s represented is how I can enjoy planning, reduce my anxiety and also keep things pretty much made up on the spot because what I’ve planned is more at the story and antagonism level and significantly less at the mechanical plot level. Since a story is not just a plot, this is entirely possible.

Planning horizons

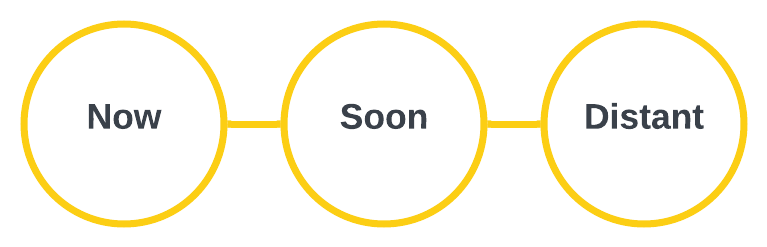

A key reason for the success of the campaign, both in terms of the content and it not collapsing, was utilising planning horizons. At any particular point in the campaign, I made sure I focused on what I needed to know now, with an eye towards soon and only an abstract fascination with the distant.

What was interesting about this approach is how it worked out in practice once it worked to control my anxiety.

The Now

The now was obvious, it was whatever potential situations and antagonists I needed for the immediate next session. This was the core of what was being planned roughly every two weeks. I used situations and antagonists for two reasons.

The situations didn’t have any defined outcomes they were waiting for the protagonists to arrive and change and drive the situation to some sort of conclusion by being their Fate Accelerated powered proactive, competent and dramatic selves.

The antagonists could be brought in as required in response to what the protagonists did because I was not being prescriptive about how any of this happened in the session. This meant I could assemble what I had as the players authored. Interestingly, because I had an eye on the soon and the distant, some things can be dragged in from there in whatever ephemeral state they were in to become locked in at the time due to player decisions. This is sort of what planning without being prescriptive looks like.

It helps that it’s easy to create things on the fly in Fate Accelerated due to its everything is a character of various complexity and the fiction first approach. This is why complex systems limit this sort of approach as it’s harder to just drag things in if realising them for the session in the rules has a certain debt of effort.

The Distant

The distant horizons manifested in a number of cool ways.

It allowed me to move things from distant to now in a way that improved how they finally manifested. As an example, I always knew I wanted a grand descent into the underworld to rescue a soul and I was playing with what that might look like as a distant, soon and now item as it moved through the horizons and in turn being influenced by the authoring in the sessions. I call this the Jabba Effect in that you late load Jabba so he can be an awesome slug rather than a portly guy in a fur coat.

The approach was immensely helpful in sticking the landing of the finale. The vast majority of the time the finale was a distant item and all I knew was it would be a grand confrontation to stop an event. Eventually, it became a distant item where I realised it needed to be like Avengers: Endgame.

The question then arose as to how you get your ‘on your left’ moment in a tabletop role-playing game?

Knowing this, shortly after the spotlights started (see planning through structure), I began to seed in situations that could be potential pay-offs and noted player authored stuff that had the same potential. Truthfully, we were doing this before I realised it’s what we were doing and it became a conscious thing a bit later down the line. One of these pay-offs went right back to the first session, which allowed for one of the biggest pay-offs with the biggest stakes.

While I didn’t know what the exact finale would look like by the time it came to the now I had all the pieces. These pieces were actually index cards given to each player of the things they could draw on. As a result, the players triggered the ‘on your left’ moments in unique ways in response to events via using the index cards of earned resources and connections.

The Soon

In practice, the soon horizon proved very ephemeral for two reasons. First, the difference between soon and distant was very ‘where does one end and the other begin’ to the point the horizons can sometimes feel like now and ‘other stuff’. Second, due to the amount of player authoring happening due to the players, the characters and the support for driving authoring and story in Fate Accelerated the soon horizon was in so much flux you could question whether it was ever in stasis enough to be useful separate from the now.

A key tool did come from the soon horizon.

If now is close to what will collapse into reality then soon is the potential of what may collapse into reality. What existed in the soon horizon was the quantum physics of what could be and I had them in mind so they could be layered into the sessions as the players did stuff that gave me permission and signals to layer them in organically. The sessions informed the soon and the soon informed the sessions in a strange quantum physics relationship.

Yeah, it’s getting a bit tripy, but it really worked as it allowed me to plan without being prescriptive. I believe this meant the campaign was actually highly planned but had none of the problems of being highly planned. I could highly plan, have an intentional story and there was zero railroading beyond that which the whole table excepted from session zero which was limited to the abstract idea they would be a werewolf pack charged with being the spearhead to stop a potential apocalypse

Planning through structure

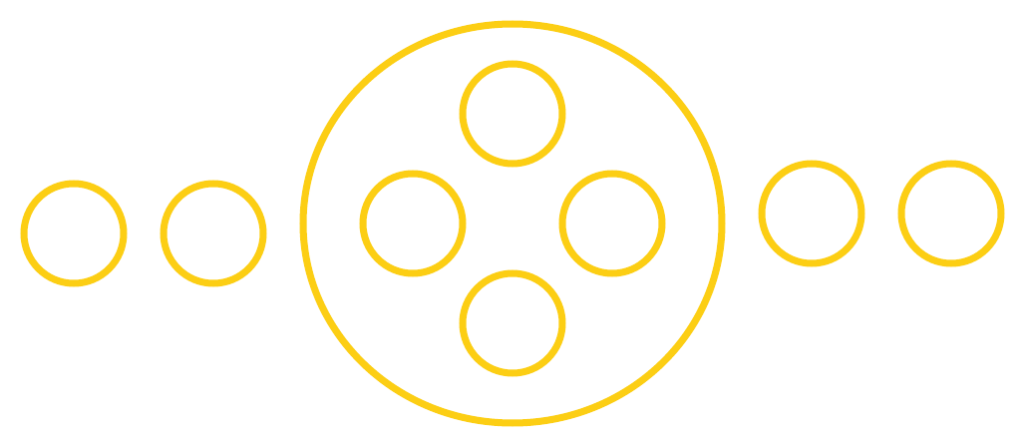

What did I know when we started. Surprisingly little. So little it’s easier to describe what I did know. In order to give me a framework to plan with, I find planning through structure helps. This means one of the key things that framed my thoughts when we started was the below diagram.

That was the campaign. A few opening sessions. A series of spotlight sessions, one for each character. The closing finale. I had no idea what those spotlight episodes would be or what the finale would look like. The key thing is the structure allowed me to plan as I knew at some point, using planning horizons, I would need to have a sense of what these things might be.

I did know what the first session would be and as agreed in session zero it would pull the characters into something immediate that would establish them as the Werewolf pack most likely to succeed against this specific approaching apocalypse.

Was this another tool to utilise planning horizons? Damned straight. I didn’t concern myself with the next phase for the majority if not all of the phase before it. Each of the phases proved slightly longer than I thought it would be. The first phase essentially set out what the campaign would truly be like more than the campaign guide.

And, Finally…

A campaign with a high degree of authoring across the table demands clear signals for everyone to react to and create. A lot of what we do before the dice drop is to establish those signals. If you look at it as establishing signals then you can be less prescriptive about things. You can shake up how you do things because what’s important is the why. You can be less focused on bibles and encyclopedic details because you’re signalling principles rather than a 100-page world history of facts.

You can plan without being descriptive by recognising what you need to know across the now, soon and distant horizons. It’s surprising what little you actually need to know ahead of time to make things deep, meaningful and intimate. You can even use structures to frame these horizons.

In this next article, After the Dice Drop, we will discuss what happens when you hit the table and how the signals, fiction first systems and a high degree of playing authoring can establish what the campaign will be at the table through dramatic choices.