Let me tell you a story. I used to get very stressed about the plot. At multiple levels. I used to like to know, as a GM, I had a plot figured out. I wasn’t tyrannical or anything. Even though I used to have it figured out down to where everything was and how specifically everything connected to everything else it would change a lot during the TTRPG session. I didn’t force the players through it.

I just needed to have gone through the process to get to the table.

You could say this whole approach to how the GM ‘plots’ is very much the outcome of personal therapy over this issue and it’s made me a much happier TTRPG person.

Important: It is very important to have read the article How The Table ‘Plots’. This entry follows on from that and mentions the themes established in that article on the assumption it’s been read.

Should the GM Have A ‘Plot’?

..actions have consequences, which in turn provoke obstacles that are commonly dubbed forces of antagonism – the sum total of all obstacles that obstruct a character in the pursuit of their desires.

— John Yorke, Into The Woods.

I guess the first question is should the GM ‘plot’? There are many people for whom the answer is no. The GM is there purely to respond to the demands of the players. I don’t hold with that, the GM always needs to bring something to the table and that inevitably involves a sense of a purpose which is often a ‘plot’. It may be a very player formed ‘plot’, as is suggested here and in the previous entry How The Table ‘Plots’, but it is still a plot of sorts.

I’d also make this argument. The players bring their imagination and their character to the game. The bring the protagonist. The GM brings their imagination and a ‘plot’ in the form of the forces of antagonism. The sense of ‘plot’ is to the GM what the character is to the player and seeing the player characters proactively, competently and dramatically engage with it and, in truth, collapse your ideas into reality, is the GM’s form of play.

Where Does My ‘Plot’ Come In?

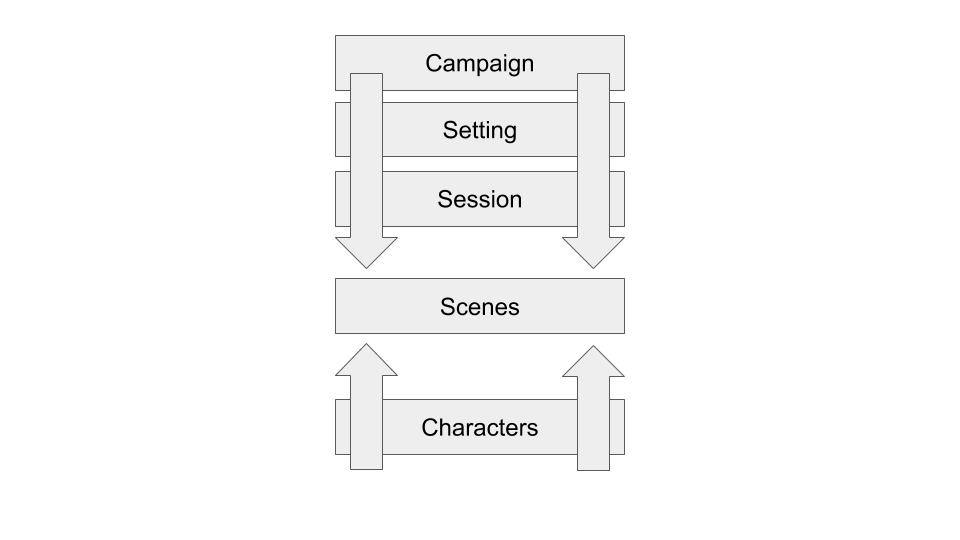

When considering how the table plots we established a diagram of how the layered signals work and responding to and mediating those responses is essentially how everyone plots at the table. You can read a further discussion of this framework in How The Table Plots.

If all the above is true where does the GM ‘plot’ come in?

What your plot can’t be is so set in stone that it’s effectively a rock-like meteorite that completely ignores all the signals that have been given, and continue to be given during play, as this means you can’t respond flexibly to the signals as you’ve essentially locked down your responses to the inflexible plot.

What you have to do is re-think about what constitutes your plot so that it becomes a tool for you to maximise your responses to the signals and be a guide for your part in mediating the responses (just like the player’s character is for them).

How The GM Plots

The key is to deconstruct your plot. I don’t mean in some arty way like ‘deconstructing the superhero story’, I mean it literally. Your plot should not be a tightly woven sequence of events that is essentially the unshiftable DNA of that meteorite.

Like we established in how the table plots there are three themes to how the GM ‘plots’, which are listed below: –

| Theme | Description |

| Facts | The facts of your plot from the smallest to the largest and the degree to which these facts are set. |

| Connections | The connecting tissue to the situations and facts and the degree to which these are in anyway set. |

| Situations | The situation where conflicts occur and decisions made and degree to which these are set. |

We can say that a plot is facts (information and clues) that are revealed in situations (or scenes) and those situations can be found via connections. The hard, destructive plot meteorite we want to avoid has all the facts absolutely set and all of those facts only to be found in specific situations in specific ways and all the connections to those situations are set as well like a map the players have to decode.

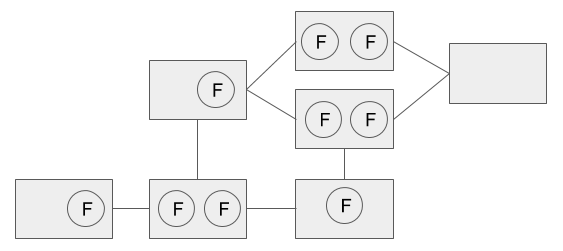

This destructive plot meteorite might look like the below: –

It is a series of hard connections to specific facts which are discovered in set situations via set means. It’s easy to see what such a set-up does to how the table plots? The whole concept of proactive, competent and dramatic characters goes out the window if nothing changes in their presence? It doesn’t matter how proactive they are, the connections and the situations remain the same? It doesn’t matter how competent they are as they’re only going to discover the clue in the right situation found via travelling along the right connection?

What happens is you effectively shift the emphasis from ‘the player character’ to ‘the player’ as it is the player who must figure out the set DNA of your plot.

So we deconstruct the plot, which involves a number of things but it’s impact on our example diagram is shown below: –

Everything in isolation and, preferably, as abstract ideas that can change. When you do this often enough you’ll even learn you just need a lot less of this stuff. You see all of this ‘stuff’ collapses into reality when observed by the player characters. It doesn’t really exist until that point. Like quantum physics, until observed by a proactive, competent and dramatic player character they exist in a state of flux and when they do collapse into reality it can be done via mediating the response to signals at the table.

In that moment, how the table plots and how the GM plot becomes the same thing and it is what constitutes play for both parties.

Can’t Stop The Signal

This remains 100% true, it’s just true in different ways when it comes how the GM plots. Signals remain everything. They also remain your friend.

In the early phases of the campaign, the campaign and setting signals can be used to ensure that they are right for the type of game you want to run. Unless you are willing to 100% respond to the signals of the players it’s not uncommon for the person running the game to have an idea of the type of game he wants to spend his time with. So it’s perfectly fine to set some of the campaign and setting signals via your pitch document or during session zero.

Just leave plenty of room for the players to set signals within your initial steer.

It’s perfectly fine to set campaign and setting signals for a Star Wars game that indicate a frontier-style western game with no Jedi. The players can still set a whole host of signals within that direction.

While you’d think the character and scene signals would be problematic as they’re either more in the moment (scene signals) or for the player to establish (character) it’s not the case. Remember these signals are all being created within the governance of the campaign and setting signals and these are very much the key ones that act as the conduit for you to collapse your ‘state of flux’ plot into reality as the response to these signals is mediated.

Those Confounding Facts

The only fact about your fact should be the actual fact. Let’s say a fact consists of: –

- The information

- Where it is

- Who knows it

- What unlocks it

You can see how this goes. The ex-wife (who / where) knows the dead husband owed money to a gangster (fact) and she might unlock it if bribed (the unlock). The secret diary of Laura Palmer reveals she had a secret boyfriend (fact) and it’s to be found in her friend’s bedroom (where) and is unlocked by searching or maybe gaining the trust of the friend (the unlock). And so on.

While you may hold onto both those facts as a default, the only element with any sense of permanency should be the fact – everything else you should consider changing in the context of mediating the signals as the game is actually played.

Proactive, competent and dramatic player characters will change things up. This is inevitable.

They will look for facts in interesting and possibly better places than you envisage. They will tie things to the growth of their characters that you didn’t expect. They may even have the power to author facts! As these signals burst forth and the responses are mediated reveal the facts and dynamics of the plot by changing where, who and how as you can bet those in the moment possibilities are way better than waiting for the player, note not the player character, to discover your set option.

Depending on how things go maybe it’s better for the dirt-bag boyfriend to have stolen the diary and instead some facts are revealed earlier through what the friend read but she only got some way through before her boyfriend stole it! Why might you change it as the session unfolds? Well, maybe one of the characters signals a relationship with the friend and this supports that? Maybe they’ve really signalled the belief (which often means they’d like) the dirt-bag boyfriend is up to something, and he wasn’t, but these signals are gold so you mediate the response to them by shifting things around.

I can say with 100% confidence that responding to the signals will get way better results than waiting for the player to find your facts in the exact forms you imagined them. The game isn’t about the player figuring out the plot, it is about the player character navigating the plot in a dramatic way.

We Don’t Need Roads

As I said at the beginning of this article, creating a structured plot for my TTRPG sessions used to stress me out. It had to make sense. As if the players were going to forensically inspect it and find it wanting. A lot of that stress was the connections, the route through the plot. I did realise my structured plot would change. I certainly didn’t stick rigidly to it, yet it still had to exist.

I now approach connections in three ways.

First, don’t view connections as something a player has to find, they are instead something a player character creates when they proactively use their competence and drama. Remember, you have proactive, competent and dramatic player characters and them routing themselves to the situations is one significant way this manifests. If you want to have some possible connections in mind just have them free floating in your head as things you can use when you mediate the response to signals at the table.

Second, don’t have hard connections and have thematic connections. This is a way of having connections that are more narrative than an if / then plot. It doesn’t matter what the connection actually is, you just have it in mind it would be handy if it somehow draws on a player character’s relationship with X or their current issue with Y. When a player signals a way to form a connection you can mediate it with this thematic element in mind and make it even more defining to the character. I often use diagrams for this, some of which I outline later.

Third, don’t create any connection ahead of time at all. Yeah, this feels really odd. How is a plot really a plot without its routing? Quantum physics remember. Since it’s only going to exist once observed by a player character just save yourself the effort. Sometimes there literally is no spoon. You should be putting your effort into situations anyway. Sometimes what you actually present as ‘plot’ is just one big situation the player characters enter from left field and…GO! At that point, there is no real plot routing, just relationships and dramatis personae.

You’d think in some game types you’d need connections more than others? Let’s use an investigation game as an example as it serves as the extreme case of connecting things to facts and having things to be discovered. You’d think that, but it’s not true. It’s not true because if you’re playing a TTRPG set-up as ‘solving a mystery’ being the primary narrative construct then your proactive, competent and dramatic player characters should be set-up for it as well.

What’s important in a mystery isn’t a player figuring out the mystery, it’s a player character dealing with the known facts or the consequences in situations. So there should be minimal barriers to the situations even in a mystery scenario.

Connections often have two elements: what and how.

So take a game where the characters are all Jason Bourne level spies embroiled in a conspiracy. The player characters still create the routes via proactively using their competence and drama to get them to the situations as fast as possible with whatever sensible approach they use. If they decide to follow the money (what) it doesn’t really matter if they hack the bank to find it (how), use human intelligence to obtain the information by bribing an employee (how) or use dramatic connections to get to a party and corner the head of bank security to threaten him (how).

You will notice the last option sounds like an actual situation? Quite true, sometimes the methods the players enact will be a quick set of skills rolls for a purely bridging connection, sometimes what they chose to do will create whole new situations which can take things in interesting directions.

The point is they will have moved on and these choices will be player character-defining and player character actions. Anything else results in potentially floundering around and asking your player, in my case a middle-aged, white guy consultant to be the super spy, or the prodigiously intelligent Wizard? Well, I’m not, that guy is on the character sheet. I can make dramatic choices for him in situations and portray the consequences once I know the facts, what I don’t have is the competence and drama to get to those situations and facts. I don’t personally have the tools the character has. I’m just a normal guy, it’s the player character who is a member of homo fictitious with the competence and drama to back that up.

The chances are the players will try something that is better, so let them create those connections.

If you feel you want things to be a bit more structured, which is probably a good suggestion for an espionage game but less so for say a superhero game, so the mystery feels like it does actually exist to be ‘figured out’, concentrate on the what and let the players define the how. You may set that they need to follow the money or discover the secret affair, how they do it is less important. Let their competency shine.

This works for any game, though I agree some games enact the proactive, competence and dramatic character model better in the rules than others.

It’s All About The Situation

Somebody’s got to want something, something’s got to be standing in their way of getting it. You do that and you’ll have a scene.

— Arron Sorkin

Situations are really a way of constructing scenes. While this does not have to be true of every scene, sometimes characters are just shooting the breeze, more often than not a scene should be a situation that needs resolving. This means a conflict that needs a resolution.

A situation is a conflict without an outcome awaiting the player characters.

This does not mean a physical combat, it just means there is some sense of multiple outcomes and the scene is a way to role-play and use the proactive, competent and dramatic character in ways that allow them to bring their competency or change their dramatic situation.

Situations are really all that is important. Even in a mystery set-up, it’s not really the finding of the facts or the connections that is important, as proactive and competent characters can do that; it’s how the characters deal with what they have found or the situations they find themselves in.

In truth, the gm ‘plot’ can actually be a handful or less of situations that you have in mind, how they get to them and, to some extent, in what order usually just sorts itself out at the table in actual play.

The key thing about situations is to present the characters with interesting choices and conflicts that are meaningful, change who, how they relate to important things or move them towards some of these things. Finding out the ex-wife committed a crime shouldn’t be the problem, deciding whether to use that information against her should? Getting the point the characters can free the soul of a mummy should be an adventure, but the true moment is the choice between that and collapsing the underworld and all the un-trescended souls within it?

It’s like the moment in Mission Impossible 2 where they find themselves in the lab, with the bad guys and the virus. How they found the virus is competency on display mixed with dramatic connections. How they got to the lab was also competent skills being used for some excitement. What is key is the situation in the lab where they meet the bad guy, have a physical conflict and a character deciding to infect themselves to secure the virus.

The GM plot is the situations, as it is where the players have to make choices. They can dramatically play their characters at that point of choice or decision once they have the facts. So that is where the focus should be. If you put the focus on figuring out the connections and the facts, you not only lock the plot structure in too much, you put the focus on the player at the wrong time, as it is the player character that is competent and dramatic.

All The Wonderful Toys

This article is very focused on lining up how the table plots and how the GM plots in order to show how author-focused play can happen. As a result, the time has been dedicated to showing how a structured plot can be broken up, trimmed down and be delivered in response to signals given by proactive, competent and dramatic characters. It leaves out a whole host of other tools for time and space in favour of addressing that theory.

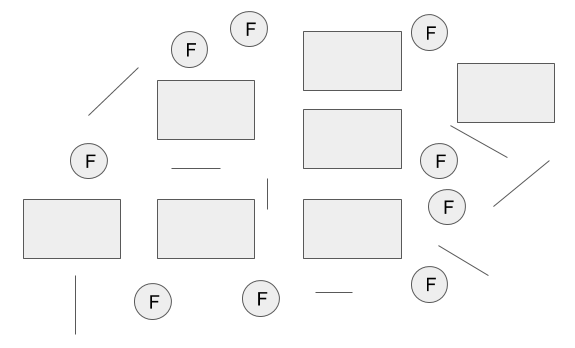

I am a big fan of diagrams though, so I thought I’d drop some in here as examples of tools that can help.

The first type of diagram I find useful is a relationship map. While I don’t believe sticking to a plot structure is useful, having an idea of how all the dramatis personae relate to each other and the characters can be useful. It acts like a spider’s web and as the players step into it they disrupt it and it changes and interesting and dramatic ways that in itself can become plot. Since I am a big fan of my ‘plot’ being about how the characters dramatically relate to people, ideas and institutions this map always exists – it’s just not often written down.

The second type of diagram is a conspiracy diagram. This is good for games where the players are investigating, well, a conspiracy. The good thing about a conspiracy diagram is it gives you a tool but it’s at a sufficiently high level that it doesn’t overly impact the at the table plotting but allows you to keep a sense of consistency to the conspiracy.

Finally, and I realise this one may be more specific to me and how I think, is I often have a sense of the campaign’s structure. It always changes a bit, gets longer or shorter, or even the structure itself might change, but it’s a bit like a plan to work to. I used a general structure for my current Werewolf Accelerated game.

All these tools are not rigid plans, but tools to allow you to navigate and respond to the signals at the table.

A Note On Homo Fictitious

Earlier in this series on author-focused play we layed out how the player characters aren’t normal people and are burdened with premise. They are dramatic, competent and proactive constructs. Possibly now you can start to see how this happens in play?

It happens because you shift being competent to the player character, and away from the player, and allow them to be competent by, to one degree or another, collapsing things into reality once they observe it and in a form contextual to the player character. It is the player being incompetent in these areas that strips away the player character feeling like one in a work of fiction. The player can bring more value in the situations by making decisions and role-playing the fall out of outcomes.

This gets you over ‘how can the characters be Homo Fictitious without the author’s guiding hand’ problem.

Then throw in the other tools we’ve mentioned like setting stakes, etc.

And, Finally…

It’s worth admitting as we come to the end that I experienced a lot of imposter syndrome writing both how the table ‘plots’ and this article. The full gamut of stuff ran through my head. I was aware it is a work built a lot on the work of others. I always feel I am telling people the obvious. At times it felt like maybe it’s all a bit crazy and it only makes sense to me.

Ultimately, I obviously got over that to the point I could write it. I personally believe I’ve learned something by condensing things into these thoughts. It seems to have worked in practice for me in my Werewolf Accelerated game. It’s, for this reason, I pushed on through as I hope the outcome of my thoughts is useful to others.

You never know.

One Reply to “How The GM ‘Plots’”