Since the death of the gaming group, my pattern of actual play is changing. It’s switched from regular, long-form play to two alternate methods. A monthly or so Day Con (we’ve played Blades in the Dark and The One Ring and Dungeons & Dragons 4E is next) and potentially moving things online.

I have mixed feelings about online play. I’ve not wracked up the vast amount of online sessions some people have but I’ve completed a couple of campaigns as a player and ran the second season of one of my campaigns online (a season being our typical campaign length).

Inevitably I’ve been considering some of the challenges of online play and how I might overcome them.

Where I’m coming from

I like to clear a few things for the purposes of context before we dive in.

First, when I say long-form play I am talking about campaigns that would still be very short. We’re looking at 6-12 sessions. The important thing is it’s regular sessions, with some spacing between them and a consistent bunch of players. If campaigns go longer, and sometimes they do, they inevitably get split into arcs / seasons of said length so a conclusion can be reached. This usually means two seasons, they rarely got to three.

Second, when I say regular play I’m talking bi-weekly. The key point is the regularity with a gap between sessions as I believe this has power. There is something about the regularity and the gap that really helps with campaigns that feature a high level of authoring across the table.

Third, the lens this article takes is how online play can hamper meaningful story, this is not the same as the plot and is primarily focused on establishing and playing out things of personal meaning to the characters. This is because that’s my focus in actual play, but some of the challenges will hinder important things in other styles of play as well.

The advantages of online

There are a number of key advantages to playing online: –

Flexible scheduling. Let’s face it, it means you can play without getting off your arse. It’s the tabletop game version of working from home, but for your leisure activities. This tends to mean people are able to get games running at more varied times. Like crazy times, such as a Sunday morning (though to me that’s a good time!).

Wider playing pool. Is this going to turn into it is ‘just like working from home’? You can recruit from an almost infinite pool! The only restriction is time zones or how willing some people are to game at crazy hours. It means you can game with a wider group from the infinite online supply or create grand coalitions of the willing from people you know from conventions and online.

Makes some games viable. I’ve been told it makes some games I’d never run no matter what the method more viable as the virtual tabletop does a lot of the heavy lifting. It also makes some a bit more challenging, like those with weird dice combinations, pools and speciality dice without an app.

These advantages, accelerated by COVID lockdowns have meant people have spread their wings online, unfettered from the locational limits of face-to-face play and gone on to play many games with many different people and this is a good thing.

The online challenges

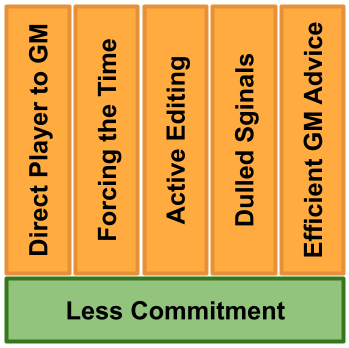

The challenges presented by online play are shown in the diagram below: –

The structure of this article is broken down in the below sections: –

- Less commitment

- Direct player to GM

- Forcing the time

- Active Editing

- Dulled signals

- Efficient GM advice

I don’t believe this is necessarily what happens in all online play, it’s recognised all of these things are a spectrum. A bit like an old graphics equaliser on a stereo they are all bouncing up and down from session to session.

Less commitment

I’ve witnessed this personally and the handful of people I speak to about their online experiences all say the commitment level for online games is often vastly different to face-to-face.

It’s easy to see why this is could be the case. It involves less effort. You can literally rock up to an online game after finishing the dishes or walking the dog. Switch on the computer and you’re in. People aren’t getting into their cars driving to someone’s home and making the effort.

I guess it feels less like a ‘date’ or an important ‘event’.

This is why online games are easier to cancel because it feels less of an event people have seriously organised their lives around. This in turn reduces engagement as people get used to coming to the experience intermittently. It’s sort of okay when it is cancelled for a while and it will come back at some point.

I’ve never experienced that feeling with face-to-face games as we usually form the group to avoid it!

Similarly, it’s easier to switch off your engagement online exactly like it is in an online meeting. It actually takes more effort to be engaged as verbal and non-verbal communication is constant and subtle in a face-to-face environment but it isn’t the case online. Also, we all have multi-screen monitors so people definitely multitask.

Since online games are more frictionless they also tend to happen at different times. There is a higher chance face-to-face games will happen on a weekend, online games can happen easier on weeknights when people may still be tired from the work day. This can reduce effective commitment due to lethargy. This is one of my biggest challenges with online games – after an intense day of decision fatigue dropping into an online game after having something to eat and walking the dog can mean I am as tired dropping into the game is easy.

Literally being asked to be creative in that skill challenge is something completely different after 4-6 hours of people hanging on your every word for significant decisions throughout the day.

This article puts forward the position that the lower commitment is the weak foundation on which all the other challenges rest and as such is partly the reason for them all. While I believe this is often true, another angle to consider is unique patterns of the other challenges actually also cause lower commitment! This can certainly be the case with individuals who start highly committed and then the challenges we are going into next erode it.

Direct player to GM

A key element of an intentional story is that the exploration of it isn’t just something explored in scenes between the GM and individual players but in scenes between players. The richness of the story never fully kicks in unless this happens sufficiently. It can work, but it’s not the best version of what could be. It would be like watching a TV show and the personal meaning that is each protagonist’s story is only explored through scenes with minor characters rather than between the primary protagonists.

While a focus on player to GM scenes isn’t unique to online play, many a face-to-face campaign can be overwhelmingly weighted to this model due to the very lack of subtle and ever-present verbal and non-verbal communication. The nature of online play can mean a high level of the player-to-player story has to be significantly intentional rather than a natural outcome of engaged, face-to-face human beings.

The result is the story moves forward less through player-to-player interaction and more through a dance of individual player direct to GM interactions.

Forcing the time

Some online games put great importance on forcing things to fit into the unit of the session.

What usually happens when the session endpoint gets close is the blunt hacking and / or cutting straight to the end. In the most extreme cases what remains is just explained directly to the players and not actually experienced by the characters in traditional play.

This makes sense if you think about it. It’s due to the foundation of lower commitment. If you have less commitment, resulting in sporadic sessions and / or people not really holding events in their head, it does make sense to make each session a complete unit and to make sure that happens as you can’t guarantee the foundation of commitment is there to support too many multi-session narratives with less clear boundaries.

In fairness, this approach is often used when the main plot beats have been dealt with, but that doesn’t mean story or rich discovery isn’t still on the table. The trouble is it often cuts across the players organically discovering ancillary things or experiencing elements of the location. It definitely cuts completely across any ‘story level’ elements of what might have been the fallout.

It removes the possibility of player authoring in these moments.

Active editing

In many ways, this is a more subtle subset of forcing the time, but it’s worth discussing specifically as active editing within a game session is quite common these days but sometimes it has adverse outcomes and this can be pronounced due to the lower commitment driving the need to hit time markers.

I’m a big fan of actively editing role-playing sessions. You can edit to get to the important bits, cut to moments of big decisions, and make sure scenes happen to support those big decisions. You don’t just want things to meander around aimlessly. The risk with active editing in a role-playing session is it can tip over into being an unintentional form of overt control of what is given time and attention.

It’s good to smash cut to the action sometimes and not deal with all the minutia leading up to it. If you’re not careful, while navigating the reduced commitment framework and feeling the need to hit temporal markers, you can literally end up using active editing as a teleportation tool that moves the characters to plot moments that they deal with and then move on.

This can exorcise the story, leaving just the mechanical plot.

Dulled signals

Story at the table is essentially a series of rolling signals that people create, receive, respond to and hand off. This is how story happens in a role-playing game (unless it’s very dictatorially GM-led), which isn’t the same as the plot. Players signal story intent, other players pick them up, scenes occur, stuff is authored and the signals change frequencies or all new signals arise and on it rolls until the story of a character concludes or changes anew.

In online games, it’s all too easy for this rich, fabric of signals to never pick up momentum assuming the people are the table are trying in the first place.

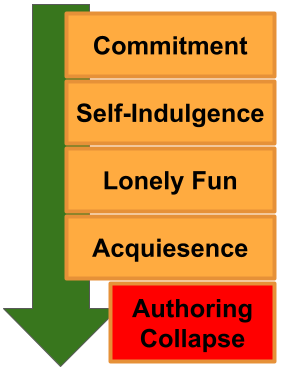

The direction of travel can look like the below: –

The players have a go at generating the right signals and playing the scenes out but the environment isn’t fertile enough for the creative fire to take hold. This tends to engender a sense of self-indulgence in those trying to maintain it. Once people feel like they are doing things out of the ordinary or their actions feel a bit ‘artsy wank’ in the fabric of the game what happens next is those trying move to lonely fun, which exists in their head at best, closely followed by them acquiescing to the signal-less environment and just giving up.

At this point, you have a player authoring collapse.

Once you reach the authoring collapse what constitutes role-playing can become role-playing as performance. This is because acting roles, utilising repeatable statements or a character’s musical riffs is something you can do independently on your own. It’s just not a story as it rarely encompasses meaningful change within the context of a goal. It’s more of a performative pattern.

The ultimate end result of this is everything devolves to being purely a game, and the roles are largely just ‘game roles’ rather than roles in the dramatic sense.

Efficient GM advice

GM advice is an interesting thing because it’s matured to the point people can use it while losing sight of where the advice is supposed to sit in the creative process.

I’m all for efficient GM advice. Any advice that strips down the amount of effort and time it takes to put a role-playing session together is a great thing. The advice is many and varied and you can find it in different forms across the internet. You’ve probably developed a bunch yourself, I know I have, and should you look into the ideas of others you’ll find they fall into common patterns verbalised in different ways.

The challenge comes when this efficient GM advice hits the hard wall of some of the other challenges. What can happen is the advice stops becoming an input and support mechanism for a creative process it instead just becomes the direct output.

The result is the patterns and methods of efficient GM advice become exposed in a rather unashamedly naked form. You can see it. You expect it. The elusive magic is removed because the creative process was never there to add it.

It’s perfectly possible to reveal what the Wizard of Oz has behind the curtain in a role-playing session, when you’re authoring across the table it sort of relies on it. We have all GM groups with high across-the-table authoring so everyone is aware of what’s behind the curtain but a creative layer is still being added.

When the pattern of each session is very clear and fatalistically repeated the players resign themselves to a Thanos-level inevitability of each session being the same in its pure, direct form. As a result, the players conform to it and they themselves begin to stop adding a creative process to it and lean in.

What’s the final result?

I tend to see all these challenges coalescing in the below statement with the problems in bold.

Due to there being less commitment inherent in online games there is a predilection to play to the format over the experience which in turn means the experience takes precedence over the story. This tends to drive role-playing towards performance as the story is squeezed out and the nature of the medium favours direct player to GM play and it naturally dulls the signals that are necessary for the rich story to happen.

While we’ve discussed less commitment, direct player to GM and the dulling of signals already, we have introduced some new phrases as they are outcomes of the challenges rather than the challenges themselves. We can address them now.

Format over the experience. The format becomes more important than the experience. There is a strong desire to conclude events in the hours allotted. This desire is seen as so valuable it means applying edits that hinder or even severely control the amount of player authoring that can occur.

Experience over story. The experience then trumps story. The sessions tend to be bereft of signals because what’s important is not the story but plot events and maybe spectacle. Experience over story becomes, at best, like the WTF moments of Game of Thrones without the story elements that actually made them breathtaking. At worst, the experience becomes a mechanical plot run similar to burning through quests in World of Warcraft.

Role-playing becomes performance as it becomes the only way to actually role-play under the format and the experience. This is about players reducing themselves to what they can control that does not rely on a fabric outside their control that doesn’t exist. As a set of quirks and repeated statements remain under their control and are out of the destructive control of the wider environment.

In the past, I’ve articulated some of my problems with some gaming as it being the use of one-shot methods within long-form play and sometimes this isn’t always a good idea. I’ve been told this isn’t necessarily true. I still think there is something in this but what’s changed is the reason for it. The reason is when you put all these challenges online play faces together the outcome can feel like a certain style of one-shot format.

Basically, a certaint type of one-shot feel is an outcome of the challenges rather than it being about one-shots specifically.

The singular challenge?

Basically, there was a reason lesser commitment was put as the foundation on which all the other challenges rest. This is because all the other problems can be directly addressed with the intention of mitigating them, but it would remain very difficult for those mitigations to work if commitment remained low..

Looking at the second season of Werewolf: Accelerated and our Star Trek Adventures campaign, both ran online, we didn’t experience any of these challenges at sufficient levels to disrupt the intentional story. Why was that? Because we carried over the commitment levels from our face-to-face games to the online format (along with other subtle things like great mic etiquette and being used to playing together which compensates for the move to video).

What would I do?

In the face of the above, what should I do if I am going to run a game online? A part of me thinks it may never happen, but since it’s one of a few options I have to address these challenges as my psychology can’t see them and then just go for it and assume things will turn out to my liking.

Nudging the commitment challenge: –

- Careful with player selection,

- Have at least one ‘ex-gaming group member’ present

- Set out clearly the approach, outcomes and framing in session zero

- Utilise short, documented support materials as part of the session zero

- Write clear session summaries as touchpoints

- Communicate between and ahead of sessions

Nudging healthy authoring signals (sorting the signals): –

- Ensure campaign-level signals are embedded in session zero

- Facilitate player authoring of setting elements

- Facilitate player authoring to have meaningful issues and relationships

- Utilise a system that has intentional story at the system level

- Ensure clear signals are on the character sheet and / or

- Ensure acting on clear signals is supported by the reward system

To shape the actual play online: –

- Utilise a system heavily skewed to play as a conversation

- Ensure layered session-level signals exist

- Leave space for the story to unfold beyond the plot

- Ask questions to foster a rich environment of signals

- Favour things unfolding naturally with an eye to session length

- Address the issues, go for the scenes and as a GM facilitate that

The interesting thing about these approaches is they are not online specific, it’s pretty much the same outline as Werewolf: Accelerated which was both face-to-face and online. This doesn’t mean they’ll work because Werewolf: Accelerated had one big advantage it was the regular gaming group who just continued their normal style of play online!

Ultimately there is only so much you can do. It’s largely a leadership issue, but not leadership in terms of giving instruction or laying out a plan, but creating the environment, the supporting artefacts and then the right prompts to allow others to generate the aligned outcomes. It’s supporting leadership.

And, Finally…

Like a lot of articles, I wasn’t very sure where this was going when I started. Similar to some other articles it went through a number of re-writes moving from a bit of a complaint piece to something more oriented to how I would address problems I see as I’d want to avoid them.

I do think online games are different for the reasons outlined and also because there is a higher chance it’s taking place with people who have not established a pattern of play by playing together for years. In this situation, the environment does become how do you foster the environment online to get the outcomes you prefer.

I’m someone with a high locus of control so I always believe it is possible to put a combination of tools, techniques, methods, communications and whatever else together to succeed within a certain frame or set of outcomes.