Ultimately, you’re making your game like quantum physics in that nothing is real until it’s observed.

– Ian O’Rourke, www.fandomlife.net

When faced with a challenge I tend to address it through fight or flight. The majority of the time I choose fight and this manifests in my self-belief that I can control my environment and I bash and plan things into sufficient shape it feels framed and controlled. If I choose flight, which is often chosen when it’s not that important, I just chose to avoid the challenge.

When it comes to activities that are totally optional, like TTRPG’s, it’s all too easy to choose flight. This is why it’s become important for me to frame, I even try to avoid the word plan, my campaigns in a way that I don’t have to contemplate it all once.

So it becomes manageable.

What Is Werewolf: Accelerated

As a way to demonstrate some of the ideas presented here I’ll sometimes reference a TTRPG campaign called Werewolf: Accelerated. This is because it’s the game I’m running at the moment and the one were I’ve used most of these ideas. I’ve used some of these ideas before but it’s in this campaign they manifest in their most recent and mature application.

Werewolf: Accelerated is essentially my take on a Werewolf: The Apocalypse (specifically 2nd edition) campaign. It was one of the many games I loved that I never got to run back in the 90’s. Like a lot of cases, I loved the core pitch, principles and concepts not so much the ridiculous amounts of background material and the rules.

As a result, I’m running it with Fate Accelerated as a distilled version of Werewolf: The Apocalypse that works for me.

What Is The Challenge?

The challenge is: –

- How to plan something without feeling the pressure of all of it

- How to plan something while realising it will all change

- How to plan while still ensuring it’s the story of the characters

Anyone involved in TTRPG’s knows these are in conflict. So what does a plan that can’t be a plan, that can’t be your story and will probably change anyway look like?

Navigation Rather Than Planning

One trick I learned a while back is sometimes you’re not seeking to create a meticulously resourced and detailed plan. Quite often this is because you can’t, usually because there is too many unknowns or changes going on. If you try to do that you’re just going to face stress and worry as you’re trying to achieve the impossible.

The other option is to accept that you’re plan will never be a meticulous route like Google Maps but what you need to set-up are the tools to allow you to navigate to the end. Instead of Sat Nav you have tools that allow you to get to the end like an intrepid explorer in the age of sail.

That’s essentially what we’re doing here.

Principles Are Important

When you can’t plan a detailed route map, you let your decisions be guided by principles. These principles guide your decisions providing the necessary consistency without the meticulous planning. What do these principles consist of? Well, they’re a mixture of statements, influences, magery and big-picture ideas.

Together you’ll find it surprising how clear they make a campaign without spending hours drawing world maps, planning out plots or coming up with pages and pages of lore.

The Werewolf: Accelerated campaign was established in a six-page document: –

- One cover page

- One as a short, introductory character monologue

- Two pages framing games concept

- Two pages of rules establishing how Werewolves work in Fate Accelerated

Basically, the what of the campaign was established in two pages, three if you include the short, introductory in character monologue.

Those three pages establish a mood. The fact is we are handling a large amount of setting material for Werewolf: The Apocalypse by only bringing in what the player’s character’s drag in as relevant. The setting is defined by themes rather than a litany of facts and maps. Then we have influences listed out across games, films, books and TV which is often a quick way to establish a mixture of tone and imagery.

Three pages of A4 to establish all that was necessary for everyone at the table to have a shared understanding so the players could create characters that were 110% on point and enhanced the campaign even before the game hit the table. Essentially moments before, as we created characters and then went straight into a prequel session.

Structure Is Re-Assuring

Since we’re not writing the story, as that will emerge through play, how do you avoid the cliff edge feeling of it all being unknown and improvisation? While some people like making everything up on the fly, I don’t enjoy that process, despite going on and to make a lot up on the fly. Once we get passed the principles mentioned earlier I resolve this dichotomy by not writing out the story, instead focusing on locking down the structure. It probably helps our campaigns tend to be short and intense rather than long and rambling.

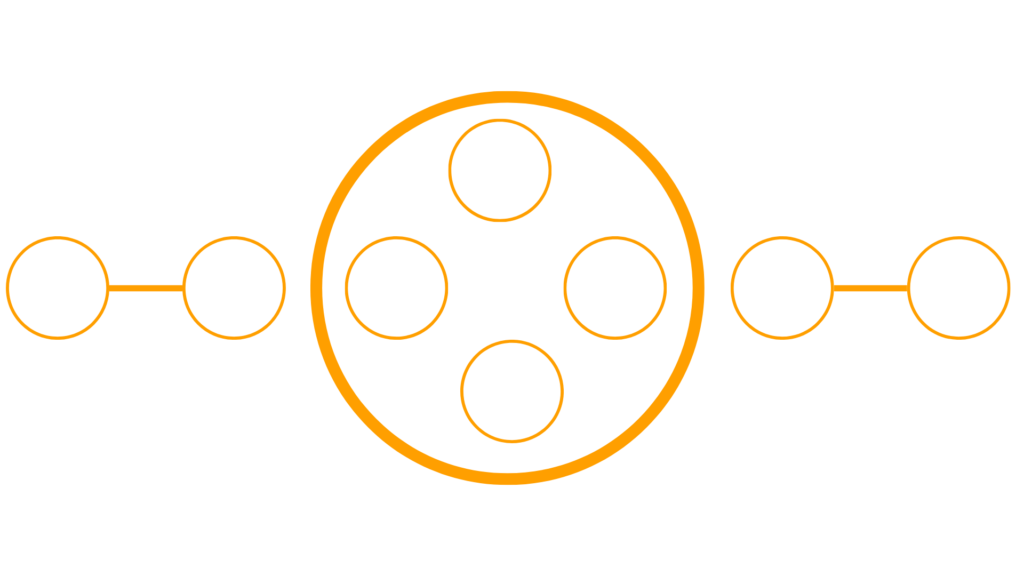

In the case of the Werewolf Accelerated campaign, I established the structure above. This keeps me grounded as it shows I have a few navigation points established: –

- A couple of sessions to establish the challenge the characters face

- Four sessions that have the characters working out the challenge (one per player)

- A couple of sessions for the resolution

It’s possible things may change slightly once things hit the table, but the structure is useful. It’s similar to how writers of a TV show usually work best when they know how many episodes they have left as they can write to the conclusion (unless they don’t have enough then you end up with Game of Thrones). In the case of a TTRPG, it’s a tool to navigate to the conclusion.

I’ll tend to have an idea of what the opening sessions might be. I will have some broad, high concept ideas on what the finale could be but accept it may change. I know what the characters will be seeking to do in the middle section but not the specifics of what the sessions will be as they’ll be highly personal to each character none of which existed at the time I established the structure.

Characters Are Key

This approach very much resides on how you see your player characters in relation to the rest of your campaign elements. Generally, you have two choices.

Do you see your player characters: –

- Plugging into an already existing, very developed campaign concept and meticulously developed setting and possibly even a relatively well-developed story.

- Being the reason everything else exists and all the important concepts, setting and story spins off totally from who and what they are.

Traditionally, many people approach it from position (1). This is for numerous reasons. It’s often how it’s been seen to be done and this is still true with the really big streaming shows. Critical Role doubles down on this very traditional approach. The setting in Critical Role exists separate from the characters and they plug into it. It’s also true that GM’s like creating settings and drawing maps and that’s fine. It does all take time though, which is one reason I avoid it.

I’d also say option (1) is chosen because people see this being the approach taken in other media, but I’d argue this isn’t true and often needs switching around in a TTRPG. This is a topic discussed in the Author Focused Play series which focuses on how principles used in writing fiction in other media can be used in your TTRPG campaigns without having a prescriptive story (actually quite the opposite).

The second option frees you up as you have to develop less upfront as you can’t until you know who the characters are. You only need enough upfront to frame a shared understanding of the type of campaign you want everyone to be creating within. Everything else spins off from the characters and may even be created wholesale by the players.

Things get exciting once you have your characters. If the bits of work you’ve done to establish a shared understanding has worked the characters presented will allow you to take things to the next level as they’ll have run with the shared understanding and created vital, proactive characters who add conflicts, setting and background elements to the game.

The beauty of it is due to the shared understanding what the characters introduced will most likely be compatible enough you can take some of your broad ideas you were thinking of and turn them into very specific character-related outcomes and they remain both your idea and the players’ idea for their characters and everyone wins.

Near, Close and Far

As a general rule, it’s best not to worry about things that are far away and may very well completely change their shape or not be relevant by the time they become front and centre. You have to be aware of the far-away things, don’t completely ignore them, but focusing on them too much leads to stress.

I approach this through recognising that my planning exists in three time horizons.

- Near: It’s the next session and I need to know what the situations are.

- Close: It’s the session or so after the next so it’s good to have some interesting possibilities.

- Far: It’s way off down the structure so keep things as broad concepts, ideas and principles.

This approach is key in keeping the game running once it hits the table as it keeps me focused only on what is important and avoids my brain over-analysing the what-ifs and buts. Each and every hour of each and every session of actual play changes the close and the far horizons as the players make decisions. This is especially true in games based around very proactive characters with rules that support that with some level of narrative control.

The Jabba Effect

Only locking things down as close to actual play as possible avoids what I call The Jabba Effect. If Jabba the Hutt had featured in A New Hope many years before he really needed to be locked down he’d have been a scruffy, portly bloke in furs. Since these scenes did not make the films cut and Jabba the Hutt got locked down in Return of the Jedi he ended up being a cool giant slug. This is why I lazy load my ideas because they invariably get better the longer they are swirling around in my brain. If I bring in things too early I often regret it.

Let me give you two clear ideas of the Jabba Effect in my Werewolf Accelerated game. The big bad they will face in the second ‘story’ has changed numerous times. It changed for the first time because I trapped a nerve in my back and had to cancel the session and I thought of a better idea while relaxing on a cruise. The visuals of the enemy and how they are are going to be realised in the rules has changed again lately due to the benefit of the players adding so much ‘story stuff’ the story has become two parts giving me more time for ideas to come to the forefront.

So that’s an example of how things change over the course of near and close planning due to not having locked down these things in the fiction at the table.

The far example is quite simple: they know a lot of the myths and legends around the big bad of the campaign but that is it. I’m quite open with the fact I’ve not fully decided what he is yet, what he is going to look like. I’ll decide these as late as makes sense because late loading them will undoubtedly make them better.

In Closing, Don’t Be Prescriptive

The theme of all this is not being prescriptive, late loading and treating it like quantum physics.

I’m not prescriptive about how things I know flow to the players, and even to some extent what they are, but I still have a sense of a story, but it’s more big situations and ideas than a prescriptive story that the players will meet and walk along. This allows my ideas to merge with the players at the table. It allows me to reveal things I want to reveal when players are proactive because I’m not prescriptive of how and when (within reason on when) they are found.

This tends to mean the game feels like radical improv from one perspective but actually planned from another.

You’re late loading because later ideas are often better than the first idea. I find the universally to be true because the richness of the game at the table increases, players get to know their characters better and as such your late loaded ideas gain the benefit of that.

Ultimately, you’re making your game like quantum physics in that nothing is real until it’s observed. This may make it sound like so little is true it will be chaos, but this isn’t the case because the players are being proactive, pushing their way forward, providing the glue through ‘who their characters are’ which means things do cement and become cohesive but in a character-driven way.