Welcome to the campaign diary of what’s been codenamed Fantasy Avengers. A campaign idea of superheroes in a fantasy setting has percolated within my brain for aeons. I occasionally pretend I’m going to run it, which no doubt gets eye rolls at best or engenders much disappointment at worst when I never get around to it.

This campaign diary will work through how the campaign gets to the table and then, with hope and a prayer, morph into actual play reports.

What this is not

This is not a review of several systems or even one. It’s a clear statement of what critical criteria I was looking for and why I chose the system I did. I also go into a few I also considered. It’s certainly not an encyclopedic assessment of what superhero systems are out there.

Critical criteria for selection

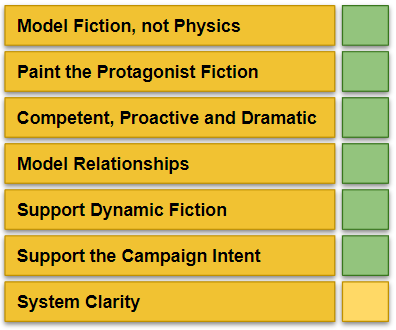

There are several critical criteria any system I choose for Fantasy Avengers must have. A bonus of writing this post is it’s the first time I’ve documented what I generally like to see in role-playing games.

Model Fiction, not Physics: The rules should model the fiction of superheroes. This is essential, and it’s why I don’t even have systems like Mutants and Masterminds or Champions in the mix, even though they’d have been candidates in the past. The exact modelling of distances and what can be lifted is just laborious, and it’s not how fiction in comics operates. I’m a big fan of Marvel Heroics’ argument that the narrative permission of a superhero’s powers exist in bands, such as super strength being normal, Captain America, Spider-man, or Thor strength.

Paint the protagonist fiction: It must be possible for a player to paint and signal the future fiction of his character in the rules. I like nothing better than painting the future potential of my character’s fiction and then playing those levers to find out. I love doing this in reverse and ensuring, supporting or providing a player with such elements for their character’s so we can all play into them. It has to be part of the rules. I want protagonist fiction to be explicit, not implied.

Competent, Proactive, and Dramatic: The system should enable and enforce each protagonist to embody these pillars in the fiction. I fully accept the theory that dramatic characters in fiction are not normal people, even if they are wrapped in those trappings. The humble maid escaping the mob because she witnessed a murder may be painted as normal, but her very position as the protagonist in the fiction makes her homo fictitious and not normal. The rules should enable this to be true through characters being competent and proactive; the only thing that should get in the way is their potential for drama.

Model Relationships: I want relationships to be meaningful. The protagonists are not islands; they will have relationships defining their choices. I need these to be represented in the game so they can drive decisions, be the fabric of bold choices, and be a mechanical element in play. I’ve said for a while now that the critical thing for my games is the passion around how dramatic characters relate to people, institutions, and ideas, and I still think that. It makes sense to embed it in the rules.

Model dynamic fiction: The rules should provide dynamic ways to model the fiction. I want varied tools to model the fiction. I will want to model enemies, antagonist resistance, fictional progress and how the Exalted face armies and vast complexes in interesting ways. Not only that, but I want to be able to switch how something will be modelled in fiction on a dime. I’ve learned from running Fate this is essential to me. I want to bring the antagonism to the game to make it interesting, but how that is represented can vary, sometimes even shifting in the same scene.

Support the campaign intent: It should be possible to embed the feel of Fantasy Avengers in the rules. This is important, but there is also a subtlety to it. It should be possible to embed the feel of Fantasy Avengers into the play experience, which may involve rules, but the rules should not subvert the Fantasy Avengers experience. I want to be able to architect the experience, not have that architecture given to me locked in.

System clarity: A system and its maths should be clear, not so clever it’s obscure. I’ve noticed this a lot lately. Systems pile on clever dice methods and multiple layers of currency, resulting in two things. The maths of success is very obscure, and things are too abstracted from even the fictional reality and the rubber band snaps. If I’m picking up the dice, I like to sense the odds, if not the specifics. I’m not looking to min-max or try to beat the odds all the time, but when we make dramatic decisions at the table, it’s nice to know the general trend of the maths as it makes it more exciting.

We’re going to use these critical criteria as a scoreboard for any system we discuss in this post.

The system is Cortex Prime

Fantasy Avengers is going to be a Cortext Prime campaign. Cortex Prime will live or die because it’s a toolbox rather than a system focused on a specific thing.

The key reason for its selection is that it’s positive for all the critical criteria, with the only complexity being the clarity of some of the maths.

When representing fiction in play, the game’s toolbox nature is its challenge and strength.

Cortex has some similarities to FATE in that there are some similarities to Aspects in some of the Traits but with dice attached. It is quite different in other ways. A key difference is the game lacks the hard decision and situation compels of FATE, but these can be added as they’re just an SFX trigger for a Plot Point.

If the toolbox has any challenges, it’s constructing the tools to be used as the rules in the campaign. This is an interesting challenge rather than a bind, especially considering the other system options. A brief document will be needed to clarify which tools have been used from the box and how they work. I’ll also need a custom character sheet. I’d love a graphically swanky one, but we’ll have to see about that.

The system is solid in how to use the rules to represent the fiction. There are different ways to model antagonists. Crises pools can represent ‘disaster threats’ or even fictional structures like fighting through a temple. Crises pools could also represent the characters beating down a small army. The threat’s ‘level’ or ‘skill’ need not be linked to the nature of the Crises Pool, representing how the power of superhero antagonists fluctuates in power. Yes, you fought hundreds in the last scene, but now the ‘fictionally more important Elite Battle Golems’ have entered the field, and the new Crises Pool is different. There is probably a way to engineer this as a consequence clock/track with failures having a selected accumulation effect. While these have not all been fully considered, the fact the options exist is great.

Relationships can be Traits, which is fantastic. Even if they’re pushed out as a Trait on the character sheet, or you want the ‘free access dice pool’ to be smaller, they can be a map of Traits accessible by spending a plot point to gain a stunt they just come with the advantage of existing dice values. This is the advantage of configuring the toolset or trait set differently.

I also love how characters have different types of stress. While yet to be decided, the concept of being able to deal with an enemy who seems physically unbeatable in the emotional balls is right on target.

The game presents some challenges regarding character creation as it has a character creation system, but it’s imperfect. The challenge with the character creation is I’d rather process some of it (the majority of traits) but leave some of it to pick within guidelines what you want (powers) and trust the players to only set things at the level the character needs. This would rely on players choosing lower die values for their powers based on concept and even accepting some characters may have a 1 or 2 more powers. I need to think about that.

The clarity of the maths isn’t completely obscure but does present some challenges. It’s unclear what the impact of larger dice pools is regarding the odds of success and the impact on the protagonists’ stress pools. What is the ‘real impact’ of using a Doom Pool or not? It seems having a D12 in the pool is dangerous. If the lower dice do well, the D12 will become the Effect Die and instantly apply D12 stress. It also seems adding dice to the total is more effective than adding dice to the pool – which doesn’t shift the odds of success in small additions. Since Plot Point generation is quite fluid, those impacts are hard to assess.

This would seem to mean there may be some calibration through play as it’s not immediately obvious what the impact of many things will be in play. For example, why would you ever construct characters like protagonists when you can construct them as dice pools? But then that removes the different types of stress to target.

The game seems to be a solid fit, even if a good bit of calibration may need to occur due to play experience.

The rejected systems

The other systems I looked at were: –

- Sentinal Comics Role-Playing Game

- Icons: Assembled Edition

What follows is a few quick notes on why they didn’t get over the line.

Sentinal Comics Role-Playing Game

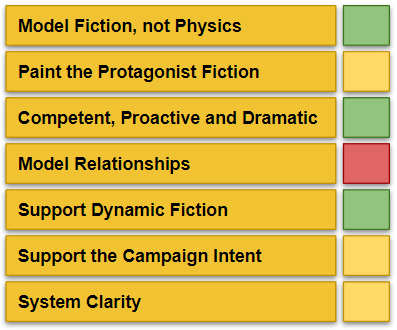

The scoreboard for the Sentinal Comics Role-Playing Game (herein SCRPG) is depicted below: –

The primary reason SCRPG didn’t get selected was it had too much structure, and that structure is based on delivering an original Silver Age experience. While that structure isn’t so oppressive, it fully breaks the support the campaign intent rule; it’s present enough I feel it’d be working against me rather than harmoniously with me. It also has zero support for model relationships, even harking back to the 90’s and suggesting social scenes should not involve dice rolls.

It does have the GYRO system, which is pure genius. This alone puts it into the running. It beautifully models how comic book superheroes become more powerful and explosive as they get beaten up. The way scenes can be constructed from different challenges, enemy types and environments, and moving through the GRYO scale, is fantastic. It takes some time to get the best out of it, but it looks worth it. It’s so good it’s the one thing I feel I lost from selecting Cortex Prime.

The whole GYRO thing is worth stealing, though I’m not exactly sure how it could be; there is a lot of similarity between Powers and Abilities in SCRPG and Powers and SFX in Cortex Prime, albeit abilities are more of a focus in SCRPG.

The system is also a bit obscure despite being influenced by FATE. It breaks the system clarity by powers being so abstracted they are opaque, and the abilities (applications of powers, etc) are just a load of clever dice tweaking. It’s not fully clear what they do or work together. I’m also not a fan of the highly structured character creation, as it frustrates me a bit when painting the protagonist fiction. It does it, but not in the way I’d prefer.

SCRPG is such an interesting beast, and it was a very close call. I want to find the time to run it as a 3-part affair with pre-generated characters to experience it.

Icons: Assembled Edition

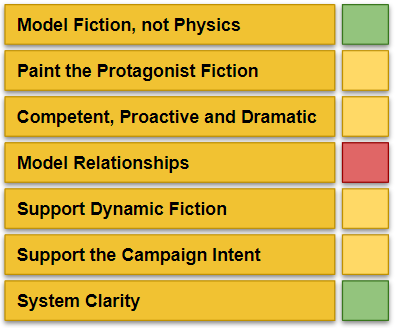

The scoreboard for Icons: Assembled Edition is depicted below: –

The main strength of Icons is its simplicity; this is also why it wasn’t selected. The game is a weird clash of FATE and the original Marvel Superhero Game, albeit I’m not sure why people attribute the second influence beyond the author.

Ultimately, I think the system would get bland. Its simplicity would transition into becoming one of those ‘slip into the background’ systems I don’t prefer. I’m also not convinced about the capability scope between characters. It feels like the power gap between characters has a harder definition when compared to Cortex Prime. I understand there are determination points and assist roles, but there seems to be something in the fluidity of characters in conflict facing more hard limits.

I wonder if Icons would become more of an option if I had more books to explore some of the embryonic ideas in the main book, but I don’t have them, and I’m not interested in finding out.

Other rejections

The old systems that used to be candidates, such as Mutants and Masterminds and Champions, because they break the Model Fiction, Not Physics rule and then go on to break all the others mostly, with a few borderline exceptions.

Similarly, I rejected the Powered by the Apocalypse games I’m familiar with because they break the support of the campaign intent criteria by often coming up with a very clear one of their own to clash with mine. Interestingly, general RPG discourse suggests SCRPG is based on FATE and Powered by the Apocalypse; I tend to see the former but am flummoxed by the latter as I write this.

A few systems that would seem to make sense that aren’t comic book superhero systems are Exalted itself and Fabula Ultima. Exalted has been rejected as the campaign isn’t Exalted. Fabula Ultima would seem to be an option, considering how there are JRPG elements in the mix. I’ve read and played Fabula Ultima, and it’s a great game, but it is a fantasy, level-based adventure game with JRPG-like tactics, which isn’t a good fit. It’s a great alternative to 13th Age for such a campaign, but not Fantasy Avengers.

And, Finally…

The system for Fantasy Avengers is Cortex Prime, and it’s been Cortex Prime for a while. The only system that’s disrupted that path has been the Sentinal Comic Role-Playing Game, which has some genius elements embedded within it. I concluded a while back that no system is perfect for this, and whichever one I choose, I will be dealing with some things I’d prefer to be different.

I need to put together the various rules in the Cortext toolset that I will use, but that’s another conversation.