I tend to read books on storytelling due to my career (martech and technology-enabled change) and personal interests. What I like to do when reading exciting books on this topic is to transpose what I have learned from one perspective to a different interest.

One such transition is taking books on storytelling in media and business and applying them to role-playing games.

Structure

The outline of this article is below: –

- The Storytelling Spectrum, which explains the concept.

- Which sounds more like a role-playing game? We establish where role-playing exists on the spectrum.

- How role-playing games are a glorious little ‘s’ storytelling conversation

- Is Big ‘S’ Truly Dead? We ask if big ‘S’ storytelling is dead to role-playing games

- Re-Engineering Big ‘S’ Storytelling, where provide examples of how to use the tools of big ‘S’ storytelling without dangerously shifting along the spectrum

- How the kickback against storytelling may be related to the spectrum

- How all this gives me a better language

Now, let’s get to the main event.

The Storytelling Spectrum

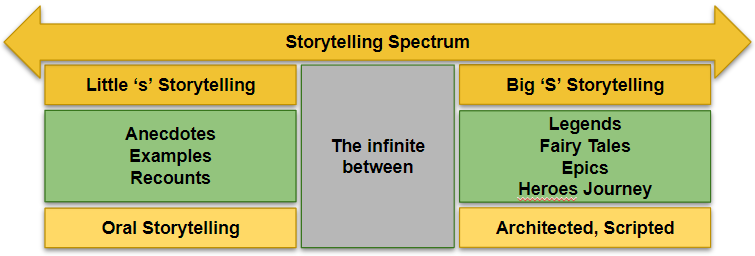

Putting Stories to Work by Shawn Callahan is focused on using storytelling in a leadership capacity, so it’s a business book. I’ve not finished it yet, but the critical thing I’ve taken from it is the argument that storytelling exists on a spectrum.

As human beings, we understand this unconsciously. The idea that the story your mate recounts down the pub isn’t the same as the latest extraordinary novel, film or TV show you’ve consumed. There is value in understanding and using something explicitly and applying it as a tool. We will do that here by describing the Storytelling Spectrum and then applying it to role-playing games.

The storytelling spectrum proposes that we have big ‘S’ storytelling at the right end and little ‘s’ storytelling at the left. From a business storytelling perspective, the idea is that what we use in business is little ‘s’ storytelling to inspire and lead, and challenges arise when you try to move it to the right.

We will go into each; what’s important is that this applies to role-playing. It applies in ways that explain why people may kick back against intentional stories, how they go wrong, and how they can go right.

Big ‘S’ Storytelling

At one end of the spectrum is big ‘S’ storytelling, which includes those elaborately crafted stories we see in movies, novels, plays and even some advertisements we see on TV.

Putting Stories to Work, Shawn Callahan (the Storyteller Spectrum idea – Mary Alice Arthur)

Big ‘S’ storytelling is the architected and written storytelling we are all familiar with in film, TV and novels. It’s big, grand, and ideally, it has multi-layered themes, complex character development, exquisitely constructed scenes and dialogue, subtext and metaphor. We could go on and on. Big ‘S’ Storytelling has all these things because of three variables: –

- The time exists to construct it.

- An individual or core team creates it.

- It’s a 1-1, delayed relationship.

You just have to read how shows like Andor, The Last of Us and Star Trek: Picard (S3) are constructed to understand the effort and architecture that needs to go into astounding big ‘S’ storytelling. It takes an intense amount of effort, and then it is experienced in a 1-1 and delayed relationship.

Small ‘s’ Storytelling

Little ‘s’ storytelling is where we find the stories we tell on a daily basis in conversations, which feature ancedotes and real-life experiences.

Putting Stories to Work, Shawn Callahan

Little ‘s’ storytelling is the oral storytelling we encounter daily, often without realising it. It’s the small stories people recount, anecdotes they tell. They are not significantly architected. Little ‘s’ storytelling is like this because of three variables: –

- They are constructed in moments.

- The impact window is narrow.

- Delivered within an immediate and dynamic relationship.

Little ‘s’ stories have an economy to their value.

When engaged in oral storytelling, we find we scale back what’s possible because it’s more effective and out of sheer practicality. We use simpler words. The language is less flowery and more to the point. The stories can also feel more concrete as they keep clear of tools like subtext and metaphor. They might even focus on stereotypes, cliches and tropes to some extent. They focus on actions, decisions and outcomes. Importantly, oral storytelling has an immediate and dynamic relationship between the person telling the story and those listening.

Which sounds more like a role-playing game?

I want to think the answer to this is obvious, as the simple truth is…

Role-playing games are little ‘s’ storytelling; the problem arise when attempts are made to turn it into big ‘S’ storytelling.

I’m not arguing that the intersection of storytelling and role-playing games is at the extreme left. If we have a goal of telling a story in our games, we are doing more than recounting and anecdotes. The role-playing experience, if it features intentional storytelling at all (as for some, it doesn’t, and that’s fine), is well into the left to the point running with the label is accurate.

When we look at role-playing this way, we can start to match the experience with little ‘s’ storytelling and then start to understand some of the challenges we see in the role-playing space that are incurred by shifting too far into big ‘S’ storytelling or using the elements of big ‘S’ storytelling in the wrong way.

A Little ‘s’ Storytelling Conversation

A role-playing session unfolds as a conversation, and if your games intend for a story to unfold, then they are a glorious, little ‘s’ storytelling conversation. I guess some people can see this as a negative, as if you look back at some of the features of little ‘s’ storytelling outlined in this very post, the terms are often negative in connotation.

To get over this, you need to consider what the expected qualities are of little ‘s’ conversation when they feature in other environments and for other purposes: –

- They’re memorable

- They convey emotion

- They’re meaningful

It’s also okay to try and move up the storytelling hierarchy within your unfolding conversation: –

- A story describes what happens

- A good story helps you see what happens

- A great story helps you feel what happens

These facets and qualities of little ‘s’ conversations are desired outcomes in other arenas where little ‘s’ storytelling is used despite their nature demanding more straightforward language, tropes, common structures and the lack of architected layers.

I don’t know about anyone else, but I want my unfolding session conversation, as a player or a GM, to be as memorable, emotional and meaningful while imparting a feeling. I’m not saying I consistently attain it, but it is the goal, whether delusional or not. I’m not in this game to assemble all my experience and knowledge of the practice for the outcome conversation not to be memorable, which ultimately rests as a basic description of what happened.

So, how do you do this? Well, by acknowledging that big ‘S’ storytelling in your unfolding conversation isn’t genuinely dead.

Is Big ‘S’ Truly Dead?

Yes, but also no.

Let’s start by outlining how it can go wrong. In Putting Stories to Work, the Uncanny Valley effect is the impact of layering in big ‘S’ storytelling into your business and leadership storytelling. The stories don’t land. They become too obtuse. They lack authenticity and immediacy. It feels false, and everyone is trying too hard. The stories’ place in the natural conversation has been lost.

An Uncanny Valley effect also happens with role-playing games; it just manifests differently, and we even have historic and recognised language for it. We have terms like railroading and lack of agency. This is when the little ‘s’ storytelling ceases to be a conversation contributed to by all, and a single individual has presumed too much ownership over the big ‘S’ storytelling tools of the trade.

It’s just hard to the point of being ruinous, a few very audience-focused player groups aside, to introduce actual big ‘S’ storytelling in a role-playing game as the form and the necessary architecture are anathema to the unfolding conversation – well unless they are part of the game rules, but let’s come back to that.

The key thing is not to architect big ‘S’ storytelling in your role-playing game but utilise some of the tools of big ‘S’ storytelling suitably re-engineered. This way you gain the benefits within the small ‘s’ storytelling conversation of a role-playing game.

The good thing about this re-engineering process is it happens all the time. People talk about it; they just don’t use this language of the storytelling spectrum. Rules are introduced into role-playing games that exist as re-engineered big ‘S’ methods. If you re-engineer some big ‘S’ storytelling correctly, railroading isn’t even possible.

Re-Engineering Big ‘S’ Storytelling

The purpose of re-engineering big ‘S’ storytelling is to take the architectural tools and make them applicable to the small ‘s’ storytelling conversation that is a role-playing session. In doing this, you’re shifting your session content to the right but not trying to make your sessions exactly the same as the pre-architected models of big ‘S’ storytelling, as that brings in the ruinous uncanny valley.

Let’s look at some examples.

What We’ve Discussed Here

As someone who likes to take stuff from one place and re-apply it to another, we’ve done some of that re-engineering on this very site: –

- We have the concept of homo fictitious from James L Frey’s How To Write A Damned Good Novel, which establishes that fictional characters are different species and never ‘just normal’ and what this means for player characters and how that can be achieved.

- When diving into Wired for Story by Lisa Cron we can apply the anatomy of a story to a role-playing game to establish how railoading should be a myth as it puts the vast majority of how a story unfolds in the conversation in the player’s control.

- We’ve also utilised Building a Story Brand by Donal Miller, a marketing book, to flesh out better the concept of dramatic characters being burdened with a premise, the story being to answer it.

Others may be dotted in the back catalogue, but these serve as examples.

Sprinkle in Methods

While you want to avoid the leaden architecture of big ‘S’ storytelling, some potential tools can be used as long as you strip them back so they are strategic, abstracted and not prescriptive. This allows you to use principles, planning through structure or things like Fronts from Dungeon World. These are all examples of planning by framing and progressing via navigation.

I did this before and after the dice dropped on my last campaign.

It’s also true some big ‘S’ storytelling techniques just don’t need a lot of scaffolding to exist in advance; an example is reincorporation. The unfolding conversation will give you all sorts of material to incorporate into the conversation later, which adds tremendous depth to the future conversation, especially if used to deliver a story of meaning with feeling.

The ending of the MCU film Endgame is one giant exercise in reincorporation for large sections of it, which I’ve also duplicated by literally and consciously logging reincorporation elements from across the campaign conversation (it helps if you document it!) for the finale of my Werewolf: Accelerated campaign.

Game Rules Re-Engineer

The games we play also re-engineer elements of the big ‘S’ storytelling toolset. The examples of this are numerous, and an encyclopedic list would be a challenging article in itself, but we can use a few examples.

Fate Apects and the compel rule, especially decision-based compels, introduce big ‘S’ storytelling potential into the small ‘s’ storytelling conversation. They reward the player for making purely drama-based decisions and represent those moments in fiction where characters make pivotal choices due to who they are. The aspect provides a level of pre-architecture without being prescriptive of how it unfolds.

The structured flashback mechanic in The Between is an excellent example of introducing the potential for players to dig deep into big ‘S’ storytelling as you can just relate a vanilla flashback, or you can dig deep into parallel storytelling, metaphor and reflection. You can do this as you (1) know the general topic in advance and (2) they happen in a set order. It is delivered in the little ‘s’ conversation but has just enough pre-architecture elements without too much shift. The Between goes even further and has a parallel story set-up, which can be artistically powerful and pushes the envelope.

These are just two examples; there are many examples across many different games and rulesets. We could go into how many Powered by the Apocalypse games embed the tropes, actions and choices of the fiction they are designed to address in the abilities on the Playbooks. As you read this, you’ll be thinking of other examples.

They are all examples of re-engineered big ‘S’ storytelling scaffolding being incorporated into the rules so they unfold in the conversation.

Kickback Against Storytelling

Some people kick back against storytelling in role-playing games. While some believe this is a fundamental principle of their playstyle and their focus is elsewhere, which is excellent, transparent and honest, some kick back against it in a way that can appear incongruent with events at their table.

Is that what they are arguing against intrusive big ‘S’ storytelling techniques? I suspect many a gamer is using little ‘s’ storytelling all the bloody time despite their vocal protests.

The storytelling spectrum can also be used to analyse why people like some games and not others. Maybe, in some cases. Again, we can use Fate as an example, as many people are turned off by the compel rule, which is the most overt, direct and shared re-engineered big ‘S’ storytelling tool in the game. Ironically, the example of the same rule is featured in many games with a Fate foundation (even if a few steps removed), but the action is less direct and accepted (because it’s a bit more to the left of the spectrum?).

It’s a complicated topic, but this is probably true in some cases.

A Better Language

This way of looking at things is a better language and understanding. I’ll leave it to others as to whether it works for them. The use of big ‘S’ storytelling language is dangerous, as big ‘S’ storytelling isn’t actually what’s happening; it’s just the best language I have.

I often describe how I run and see role-playing games playing out as a script read but with the script being authored by all at the table at the point of actual play. I think that’s a decent way of describing it. I’m also trying to do this as a player in whatever capacity. The trouble is it’s laden with a bit of big ‘S’ storytelling language.

It’s dangerous to use big ‘S’ storytelling language as it opens me up to being guilty, even if not by design, of people using heavy-handed tools at the table. I’m safe because I don’t believe these posts influence anyone – but best avoided.

The idea of keeping to the little ‘s’ storytelling conversation but with re-engineered big ‘S’ tools provides a better framework to move forward and further integrate things into how I approach role-playing games.

And, Finally…

If your goal is an intentional story in your unfolding conversation at the table, you face the dichotomy of it being a small ‘s’ storytelling medium with aspirations of meeting some of those big ‘S’ storytelling goals. You also want to maximise the qualities of the conversation and move up the story hierarchy.

And that is fine.

You just have to embrace the glorious nature of the small ‘s’ storytelling conversation and contextually and appropriately add re-engineered tools and techniques from the big ‘S’ storytelling playbook to nudge your conversation a bit more to the right. Not too far and too orchestrated, as all at the table create the conversation, and you want to avoid the uncanny valley but just far enough.

While many people will disagree, I believe the results can be great.