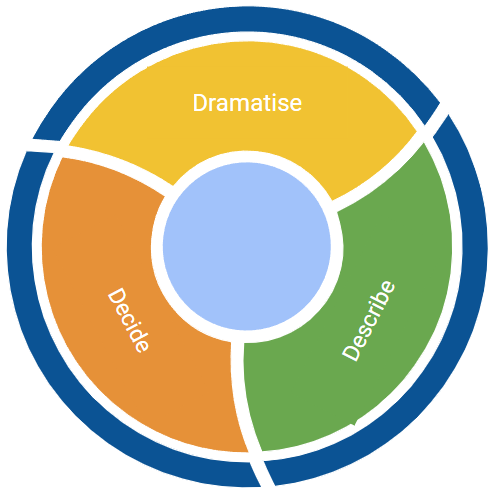

This article is inspired by posts on Bluesky discussing why players don’t role-play. The initial posts had the usual problem of presuming only certain things are role-playing. When contributing to that discussion, I realized I view things through the pillars of dramatising, describing, and deciding.

I think this makes sense. So many weeks on, I will finally explain it here.

Models Aren’t Perfect

Let’s be clear: models aren’t perfect. They are purely a way to enhance understanding or to facilitate conversation. They don’t have to describe everything in a way everyone finds perfect. This was true of GNS theory, how people see things like ‘traditional’ role-playing, story games, OSR and whatever else—it’s undoubtedly true of seeing things as dramatise, describe, and decide.

It will either help you understand how you approach and view role-playing games, or it won’t, and that’s all that matters.

Players Don’t Role-Play!

The trouble with exclamations that players don’t role-play is that they invariably mean they aren’t acting. They aren’t sitting around the table speaking as their character, potentially with accents, just having things out dramatically. Quite often, the expectation is that this should be happening even when there is little purpose to do so.

Is this surprising? You’ve probably got Dave, the project manager, Kate from HMRC, Geoff from marketing, Paula from IT, and whatever else. Hell, I’ve sprinkled in a 50% female split. In many cases, if you go back far enough, there is a high chance they’d all be male.

None of them are doing stage plays or voice acting. You won’t get anything close to the improvised scene construction of Critical Role.

The more realistic call out is the players don’t ‘play out the scenes’. It’s not about acting specifically, but more that they focus on the action or sit in third-person. My characters ‘does this’ rather than role-playing doing it in the first person.

The first-person, act-the-scene zealots don’t get that role-playing at the table is a three-part construct. All three parts are valid, and people will have different distributions.

Dramatise, Describe and Decide

Okay, so here we go. I view things through the pillars of dramatise, describe, and decide. The best way to view this is not as a priority order but as three equally valid approaches that different people will weight differently.

If there is a sweeping statement I would make, it’s that an approach to role-playing that does not include all three elements can feel a bit ‘janky’. As an example, someone who describes and decides but never dramatises a scene directly in the third person can sometimes feel a bit like lonely fun. Someone who dramatises a lot but in ways that never involve third-person description or reaching any decision? This can feel a bit self-indulgent and lacking in purpose.

Dramatise

“to present or represent in a dramatic manner”

Most people associate this with role-playing, especially back in the day, and actual plays like Critical Role exemplify it. It’s about acting out the scene, putting your character into the performance. It possibly involves accents, repeatable mannerisms, or schticks.

In the ‘days of yore’, certain traditional role-playing groups would ‘play the adventure’ and then ‘do the role-playing outside of the adventure’ as if the two should never meet.

Describe

“to represent or give an account of in words”

This is about describing things. It can be how your character looks, speaks, or performs action scenes, but it could also be about how the character feels in the scene. This is about bringing the descriptions that might appear in novels to the play experience or what might be noted in a script so that more of the character comes into the experience.

Decide

“to make a final choice or judgment about”

Your character is a protagonist, and a protagonist should make fateful decisions that matter, right? This is about setting up your character to make those fateful decisions with the help of others, which will advance your character as a person with feelings, beliefs, and things that matter.

I realise that some models of play reject the idea that a character is a fictional protagonist. However, even if this is true, you still want your character to be making exciting decisions in some fashion.

Where Do I Sit?

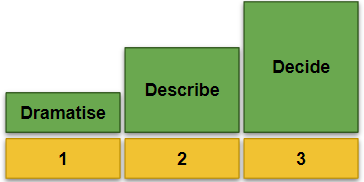

Since I’ve proposed the idea, I should lay out where I sit. Let’s assume we have six points to distribute between the three pillars, and you must assign at least one point to every pillar. Other point distributions might be better, but let’s just run with it.

I’d distribute my points as per the diagram below: –

I’m all about reaching the big, dramatic choice or judgment. If I’m playing a role-playing game, describing things, and even playing first-person in scenes, but none of it leads to fateful decisions, I don’t see the point and see it as a self-indulgent waste of time. This is how characters progress. They make fateful decisions that change them, others and the world around them. Since I focus on defining my characters through a premise, each decision is a step towards answering the premise.

I will focus on description and directorial instructions since I approach role-playing as a writer, not an actor. I like describing how things look in action scenes with a lot of physicality. I firmly believe a character is as much about their appearance, dress, and how they act as their accent. This probably helps almost all our campaigns have ‘superhero’ elements, even if it is just characters who tend to have consistent ‘outfits’ and ‘looks’.

Even in scenes that are more intimate and just people talking in a room, I’ll give visual indicators and descriptions outside of what is said. This is obvious when you think about it—actors are capable of putting it in the scene as part of the performance, but I’m (a) not up to that, and (b) even if I was better, we’re sat around a table in Bob’s house.

I still want to play out scenes; one of my mantras is to play the damned scene which can sometimes not happen at the table. I think this supports reaching a dramatic choice or judgement – not in all scenes, but from a writing perspective again; I’m looking at them to build to one.

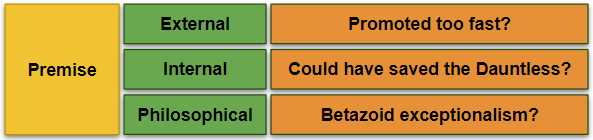

Throwing In Premise

While not core to the three pillars, it supports why I distribute them the way I do, so it’s worth bringing up how I focus on the premise. I describe how I do this in the importance of premise, which I stole from three sources.

While I didn’t explicitly lay this out for the Star Trek: Final Frontier campaign, this is the premise of my starship captain character for that campaign. It was set in our extrapolation of the Kelvinverse, so I established the Betezoids had a whole ‘Betazoid exceptionalism’ thing going in, believing they could never fully integrate with races whose minds are silent—hence the third one.

Can you see how focusing on this impacts my distribution of the pillars?

I focus on decide because it is the individual decisions the character makes (and those around them) that move the character closer to finally answering the questions in the premise.

I favour describing because communicating and navigating some of the premise’s more subtle internal and philosophical questions can be hard to do with ‘just the performance’. So, I rely on description, like it might appear in a book or a script, to communicate some of this subtly.

I still have a wish to dramatise because I do want to play the damned scenes that get the character from one place to another, but it can be easily seen, considering my acting chops, how the other two are more prominent.

It can also mean I struggle with campaigns when role-playing seems to be an exercise in itself, a dramatised performance, or something that happens around the plot or to figure out the plot.

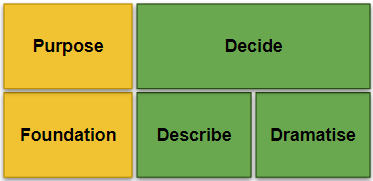

Is it a pyramid?

This is where I take the argument to a place fewer people may agree with, as it’s a lot more prescriptive. I think the true purpose of role-playing is in the decisions; dramatising and describing are foundations below it rather than the primary objective.

Decide is where the change is, whether within your character or the external environment around them. Happily describing and dramatising while not driving to any decision lacks purpose or energy. At most, it could be like playing a musical instrument and performing outstandingly, something others react to, rather than being an agent of change yourself.

The principle of giving players a lot of agency is predicated on the fact that reaching fateful decisions is what it’s all about, and you work the foundation to get to those decisions—it’s where the work is done.

And, Finally…

This is how I see the pillars of role-playing. I think it’s different and more valuable to me than alternatives like actor, author, and director stances, which tend to deal more with what the player is willing to assume they can take control of in the game.

As stated, it’s not designed to be perfect, but seeing and experiencing people’s play, I can see how some people have different weightings between dramatising, describing and deciding. It’s not just players, as the GM will have a preference, which can lead to their expectations in their interactions with you as a player. If the GM isn’t very decide-focused, they might completely miss that your actions are supporting the flow of the scene to lead to decisions within the scene itself or decisions down the line.